A Waikato landfill fire is the latest in a series of blazes suspected to have been caused by wrongly disposed lithium-ion batteries.

The fire has re-opened discussion on how we can best deal with the growing problem of dangerous battery waste.

The SMC asked experts to comment.

Professor Saeid Baroutian, Faculty of Engineering & Design, University of Auckland, comments:

How can we better dispose of used lithium batteries?

“The best disposal solution is always prevention: keep lithium-ion batteries out of general rubbish and recycling. Use retailer take‑back, council collection, or specialist battery drop‑off points. For safe storage/transport, isolate terminals (e.g., tape or bag batteries), keep them separate in non‑metal packaging, and isolate damaged/swollen batteries.”

Why are lithium battery fires so dangerous?

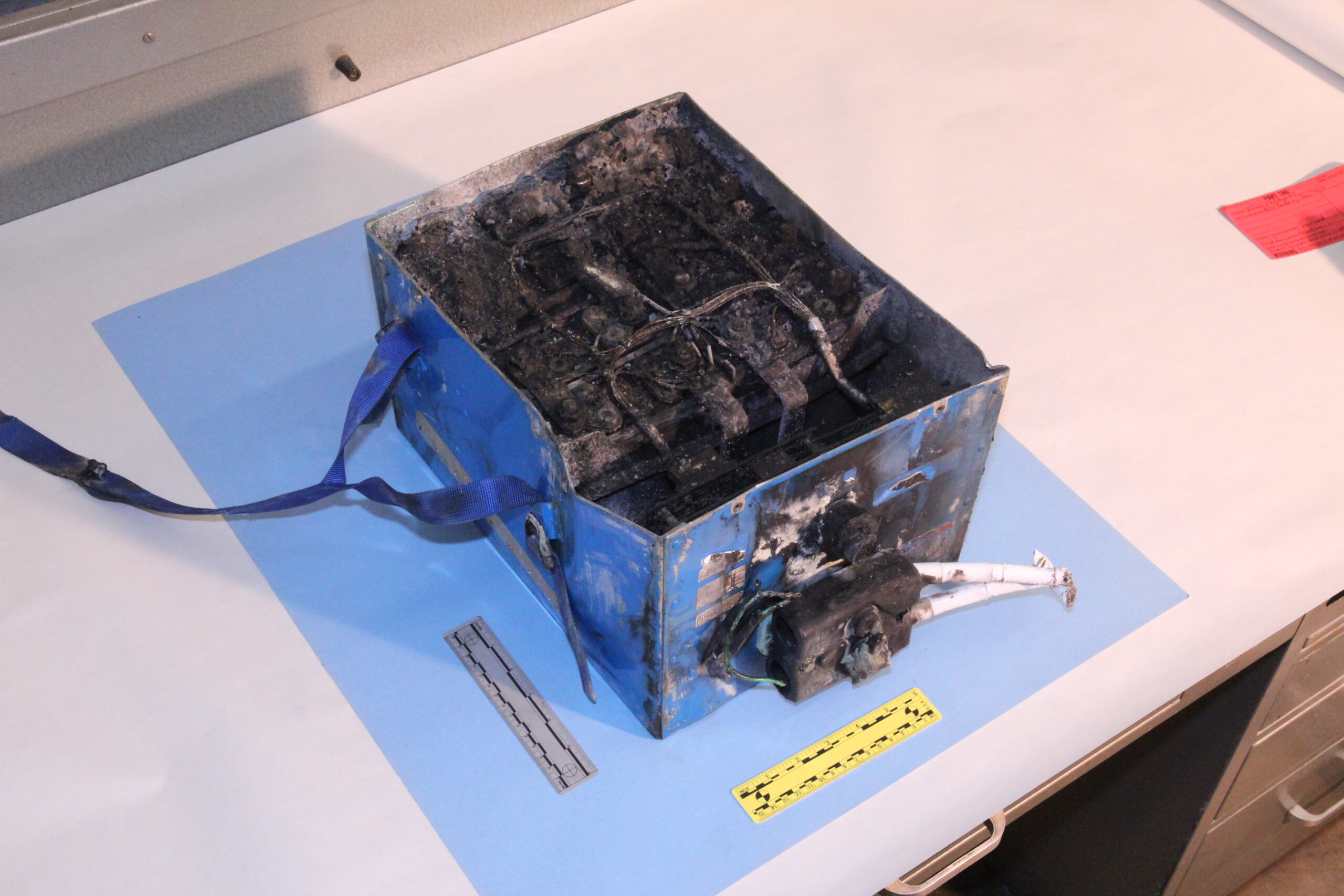

“A lithium‑ion battery fire at a landfill is not a normal rubbish fire. These fires can enter thermal runaway, they burn very hot, can re-ignite, and may keep releasing gas even after the flames are out. The smoke can contain highly toxic gases, and contaminated runoff can threaten waterways. In our rubbish-truck fire trials with Auckland Council, we measured spikes of highly toxic gases, such as hydrogen fluoride, and found that the extinguishing firewater carried fluoride and metals, showing why batteries need a separate, controlled collection stream, not landfill.”

What have we learned about lithium batteries since they were first made available in the 1990s?

“Compared with the 90s, lithium‑ion batteries are now in everyday items such as vapes, electronic devices, phones, and hand tools, and larger, higher‑energy packs such as e‑bikes, scooters, and EVs. Since the 90s, we have learnt far more about how batteries fail especially when crushed, how long they can off-gas after suppression, and how hazardous the emissions and runoff can be, so it is just a small battery is a dangerous myth.

“We have also learned that today’s wide range of chemistries, sizes, and pack designs makes sorting and recycling far harder than people assume. Batteries are often embedded, glued, or sealed inside products, so they are easy to miss and difficult to remove safely. Different chemistries and formats can require different recycling routes, and mixed/hidden designs increase contamination and costs, while also increasing the chance that a battery gets damaged during collection and processing.”

What’s driving the increase in lithium battery fires?

“The increase is mainly in volume and behaviour. There are far more battery-powered products in everyday items such as vapes, electronic devices, phones, and hand tools, and larger, higher‑energy packs such as e‑bikes, scooters, and EVs. There are more small batteries hidden in items, and too many are being thrown in household bins where they are crushed during collection or processing.

“Vapes matter because they are common, small, less protected, easily binned, and hard to spot on sorting lines.

“This is preventable, but it needs both public action and system change, clear labelling, convenient take-back everywhere, and stronger product stewardship rules.”

Conflict of interest statement: “I don’t have any COI.”

Dr Joseph Nelson (Ngāti Tūwharetoa, Ngāti Raukawa), Research Scientist, Lincoln Agritech; and Associate Investigator, MacDiarmid Institute for Advanced Materials and Nanotechnology, comments:

How can we better dispose of used lithium batteries?

“We’ve really got two options with these batteries: recycle or landfill. Recycling is the preferred option – there’s a lot of valuable metals and components inside batteries, and it’d be great not to simply lose those to landfill. As it stands though, current recycling processes are complex and energy-intensive – although we are getting better at it! But what this means is that a lot of lithium battery waste is still ending up in landfill.”

Why are lithium battery fires so dangerous?

“Lithium batteries contain highly flammable liquids. If that liquid escapes through a break in the battery casing, it triggers a very hot (sometimes explosive) self-sustaining fire that is difficult to extinguish. Battery fires also release toxic gases. This is a big safety issue, especially for those working in waste disposal, who might be caught unaware by improperly disposed batteries.”

What have we learned about lithium batteries since they were first made available in the 1990s? And what’s driving the increase in lithium battery fires?

“The functioning of modern lithium batteries is really the same as early batteries from the 90s. However, today’s batteries are a lot more energy-dense than their 90s counterparts – and they are much, much more prevalent now. Consequently, we’re seeing ever-increasing volumes of lithium battery waste being incorrectly dumped and causing fires. Single-use vapes and other small electronic devices are, unfortunately, a rapidly-growing part of this waste problem.”

Are there safer alternatives to lithium batteries?

“As well as existing battery waste, it’s important to think about what future lithium batteries should look like. We’re involved in research funded by the Marsden Fund to look at new, environmentally friendly, safer materials that can go into next-generation batteries. The ideal battery is ‘safe and sustainable by design’, with thought given to the entire life cycle of the battery.”

Conflict of interest statement: “Apart from the Marsden research into new battery materials – I am not aware of any conflicts of interest.”

Dr Julie Trafford, Associate Professor for Planetary Health, Auckland University of Technology, comments:

How can we better dispose of used lithium batteries?

“The most effective solution to disposing of used lithium batteries is recycling, to recover and reuse valuable materials like lithium, cobalt, nickel, copper, and graphite. Recycling prevents these materials from entering landfills and reduces the need for new mining. Batteries could be taken back by businesses or collected by specialist facilities for recycling.

“More environmentally friendly recycling technologies are emerging, including water- and carbon dioxide-based processes, which reduce toxic waste and improve metal recovery.

Why are lithium battery fires so dangerous?

“Lithium-ion battery fires are dangerous because they burn at extremely high temperatures and are driven by thermal runaway, a chain reaction where the battery overheats, vents flammable gases, and can ignite or explode. These fires generate their own oxygen, continuing to burn even though they appear to be extinguished. They also release toxic and carcinogenic gases that pose environmental and health risks.

What have we learned about lithium batteries since they were first made available in the 1990s?

“Long-term environmental and health impacts from improper disposal and fires are far greater than originally understood.

“Lithium-ion fires behave differently from traditional fires, requiring specialised management.

“As battery-powered tools, device and vehicle use has increased, responsible recycling is essential. Key battery minerals – including lithium, cobalt, and nickel – are limited in supply but critical for our modern electronics-based energy systems.”

What’s driving the increase in lithium battery fires?

“Leaving batteries charging unattended; overcharging; charging with an unsuitable charger; or re-using batteries for an alternative application for which they were not intended; can cause overheating and lead to thermal runaway.

“Improper disposal into household or council rubbish or recycling bins. Batteries crushed, pierced or otherwise damaged, can ignite in bins, trucks, recycling stations, landfills, etc.

“Vapes, containing low-quality lithium-ion batteries and discarded incorrectly, add to fire incidents.

“Households should use e-waste or battery drop-off points. As battery use continues to grow, safe charging habits and proper disposal are key to reducing fires and protecting homes, road users, waste facilities, and emergency responders.”

Conflict of interest statement: “I have no real or perceived conflicts of interest to declare.”

Dr Shanghai Wei, Senior Lecturer, Dept of Chemical & Materials Engineering, University of Auckland; and Associate Investigator of MacDiarmid Institute for Advanced Materials and Nanotechnology, comments:

How can we better dispose of used lithium batteries?

“Ideally, all used lithium-based batteries should be recycled and repurposed, as they contain high-value components such as nickel and cobalt in lithium-ion batteries, or lithium metal in lithium-based primary (non-rechargeable) batteries.

“In the last few years, extensive research and development have been conducted in this area, and many companies, including Mint Innovation, a New Zealand company, are working to develop waste-to-value solutions.

“In the short term, councils and local communities need to invest more in lithium-ion battery disposal facilities and public education.

“In the long term, battery manufacturers – as well as companies that produce electronic devices with integrated lithium-ion batteries – should take greater responsibility for the proper disposal and recycling of these batteries. Manufacturers should adopt a closed-loop system that includes battery manufacturing, regular operation guidelines, and disposal protocols. All batteries would be labelled with a barcode, which could be scanned to access essential information such as disposal instructions and designated drop-off locations.”

Why are lithium battery fires so dangerous?

“Lithium-ion battery fires differ significantly from regular fires in terms of causes, behaviour, hazards, and suppression methods.

Lithium-ion battery fires are chemical-based and self-oxidising. They can go from smoke to full ignition extremely quickly (often in less than 10 seconds), and are difficult to control. They also release highly toxic gases during combustion. Therefore, each recycling or waste plant should have a professional team to manage the disposal and recycling of these batteries, and which should work closely with fire management services, battery recycling facilities, and battery manufacturers – especially those dealing with large-scale batteries.

“Traditional fire extinguishers, such as water, foam, or dry chemicals, are ineffective at extinguishing lithium-ion battery fires, so those working with such batteries need a particular type of fire extinguisher, and workers must be able to access them within seconds.”

“To sum up, there are four main characteristics of lithium battery fires that make them so dangerous:

- Lithium battery fires are chemical-based and involve chemical chain reactions (also known as thermal runaway), which are fundamentally different from ordinary fires. Modern lithium batteries are designed and developed for high energy density, aiming to provide high voltage and high power in a very small size. For example, a vape device can be powered by a small lithium-ion pouch cell or cylindrical cell. However, such pouch or cylindrical cells contain many layers of electrode materials and electrolyte to achieve a high capacity of around 400–1500 mAh. If a used vape device with integrated lithium batteries is disposed of improperly, thermal runaway can be triggered by mechanical damage to the protective casing during crushing of the waste.

- Toxic and flammable gases can be released when lithium batteries are on fire.

- Lithium battery fires progress very quickly from smoke to full ignition and are extremely difficult to control.

- Existing fire extinguishing tools are not effective against lithium battery fires. A special fire extinguisher is required, but the cost is high (approximately five times higher than that of a traditional extinguisher).”

What have we learned about lithium batteries since they were first made available in the 1990s?

“Battery performance, including energy density, cycle life, and rate performance, and the costs of lithium batteries have significantly improved since the 1990s. Volumetric energy density has increased threefold, while cost has been reduced approximately 97% since the first commercial cell.

“We now have a much better understanding of the safety risks and failure mechanisms. We understand the solid-electrolyte interphase in lithium batteries and how it determines cycle life, self-discharge, and safety. The thermal runaway mechanisms in lithium batteries have also been intensively studied. As a result, we are now able to design and develop much better thermal management systems for large batteries. Therefore, lithium batteries can serve as large-scale power sources for electric vehicles and even for sub-grid energy storage.

“Global battery manufacturing and its supply chains, such as lithium, nickel, and cobalt, have become important geopolitical considerations and now influence national strategies.”

What’s driving the increase in lithium battery fires?

“I think this is mainly due to the following reasons:

- Rapidly increasing usage of lithium batteries in all sorts of electronic devices that we can imagine.

- The price of lithium batteries has significantly decreased since the 1990s; in particular, the lithium-ion battery pack price was reduced from $1,191 per kilowatt-hour (kWh) in 2010 to only $108 per kWh in December 2025.

- Lithium batteries have much better performance in terms of voltage, capacity, cycling, and rate performance than other commercial batteries. For example, the capacity of lithium-ion batteries is at least two times higher than that of Ni-MH batteries, and the voltage is three times higher than that of Ni-MH batteries.

- Inappropriate disposal of lithium batteries or electronic devices that contain integrated lithium batteries, such as vapes. End users or consumers of electronic devices probably do not know where and how to dispose of lithium batteries properly.”

Conflict of interest statement: “I declare that I have no conflicts of interest and has no financial or personal relationships that could have influenced the preparation of this commentary.”