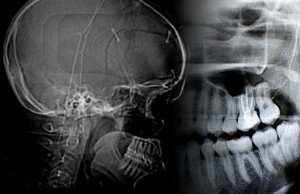

New research has drawn a link between a history dental x-ray imaging and incidence of meningioma, a type of brain tumor — but experts note that advances in x-ray equipment, regulations and the low actual incidence of the disease mean that people should not be worried about the health risks.

The new study, published in the journal Cancer, analysed data from 1,433 patients with meninginoma and 1,350 similar, but cancer-free, controls . Researchers found that, over a lifetime, patients with meningioma were more than twice as likely as controls to report having ever had a bitewing exam, which uses an x-ray film held in place by a tab between the teeth. Individuals who reported receiving bitewing exams on a yearly or more frequent basis were 1.4 to 1.9 times as likely to develop meningioma as controls.

The new study, published in the journal Cancer, analysed data from 1,433 patients with meninginoma and 1,350 similar, but cancer-free, controls . Researchers found that, over a lifetime, patients with meningioma were more than twice as likely as controls to report having ever had a bitewing exam, which uses an x-ray film held in place by a tab between the teeth. Individuals who reported receiving bitewing exams on a yearly or more frequent basis were 1.4 to 1.9 times as likely to develop meningioma as controls.

An even stronger association was seen between meninginoma and Panorex exams (which are taken outside of the mouth and show all of the teeth on one film). Individuals who reported receiving these exams when they were younger than 10 years old had a 4.9 times increased risk of developing meningioma. Those who reported receiving them on a yearly or more frequent basis were 2.7 to 3.0 times (depending on age) as likely to develop meningioma as controls.

However, The researchers noted that today’s dental patients are exposed to lower doses of radiation than in the past. Nonetheless, “the study presents an ideal opportunity in public health to increase awareness regarding the optimal use of dental x-rays, which unlike many risk factors is modifiable,” said lead researcher Dr. Elizabeth Claus. “Specifically, the American Dental Association’s guidelines for heathy persons suggest that children receive 1 x-ray every 1-2 years, teens receive 1 x-ray every 1.5-3 years, and adults receive 1 x-ray every 2-3 years. Widespread dissemination of this information allows for increased dialogue between patients and their health care providers.”

Our colleagues at the UK SMC collected the following expert commentary. Feel free to use these quotes in your reporting. If you would like to contact a New Zealand expert, please contact the SMC (04 499 5476; smc@sciencemediacentre.co.nz).

Prof Malcolm Sperrin, Director Of Medical Physics at Royal Berkshire Hospital, said:

“Ionising radiation from any source is known to have a potential health detriment although the very low radiation dose leads to an overall risk that is extremely small. That being said, this paper does provide sensible statistical evidence for a correlation between dental radiation exposure and the incidence of meningioma. Howard, caution is needed in interpreting the conclusions since there is no data that summarises the radiation exposure to the patients. The paper does state that the findings relate to older, higher exposures and the overall intention is to raise awareness of risk factors which is commendable.

“Current best practice suggests a fatal risk of 6% per Sievert of radiation. In the UK a ‘typical’ dental X-ray causes a radiation dose of typically 0.005mSv or a fatal risk of 1 in 40 million. Whilst data varies with source, the likely incidence of meningioma is around 1 in 10000 hence radiation-induced effects are unlikely (but not impossible). It is important to realise that under UK legislation a thorough risk assessment is conducted before anyone is exposed to a source of ionising radiation and there is no reason for a patient, or relative of a patient, to be concerned by the findings of this paper.”

Dr Paul Pharoah, Reader in Cancer Epidemiology at the University of Cambridge, said:

“Meningioma is a rare form of benign cancer that affects the lining of the inside of the skull. The tumours are usually slow growing but can sometimes cause problems if they start to press on the brain.

“The disease is rare. It affects two to three people in every 100,000 in the UK every year. The lifetime risk of the disease is about 1.5 in a thousand, and it is approximately twice as common in women as it is in men.

“Ionizing radiation in large doses is a well-established risk factor for the disease, but the effects of lower dose ionising radiation – the sort of dose that comes from an X-ray – was not known.

“The study reported in Cancer has compared a large number of people with meningioma with a similar number of matched healthy individuals. The study has been carefully designed and is well-conducted. The analysis is sound. Bias is always a potential problem in case-control studies, but this is unlikely to have been a major problem in this study. The authors report that dental X-rays are associated with a small relative increase in risk of disease of approximately 50 percent or 1.5-fold. This finding is statistically significant.

“However, as the disease is rare, the increase in absolute risk is tiny – the lifetime risk increasing from 15 in every ten thousand people to 22 in ten thousand.

“People who have had dental X-rays do not need to worry about the health risks of those X-rays. Nevertheless, dental X-rays should only be used when there is a clear clinical need in order to prevent unnecessary exposure to ionising radiation.”

Professor Dame Valerie Beral FRS, Cancer Epidemiology Unit at the University of Oxford, said:

“I am familiar with this type of research, where people with known brain (or other) cancer are asked, in retrospect, how many X-rays they had had in the past. The responses about X-ray history in people with cancer are then compared with those of healthy people.

“There is known to be poor agreement between people’s recall of past X-rays and records of X-rays actually done. Furthermore there is considerable scope for different recall of past X-rays by people with and without cancer. The authors of this paper did not check whether the X-rays reported agreed with X-rays actually done. Hence their findings could be simply due to different reporting of past X-rays by those with and without cancer, rather than any true difference in exposure to X-rays.

“Other studies like this one have been done before, but the findings from all such studies are difficult to interpret for the reasons given above. Reliable evidence can come only from studies that use recorded information on X-rays done (not reported exposures to X-rays long ago) in people with and without cancer.”

The UK SMC also provided this helpful statistical review from their Before the Headlines team:

—————– —————– —————–

Title, Date of Publication & Journal: Dental X-Rays and Risk of Meningioma, 0500hrs Tue 10 April 2012, Cancer

Claim supported by evidence?

This paper lends broad support to the claim that exposure to dental x-rays may be associated with increased risk of intracranial meningioma, though does not use the necessary study design nor provide a sufficient depth of analysis and discussion to infer a causal link between the two.

While there is a generally consistent finding relating increased risk to higher frequency of exposure at younger ages, the analyses do not account for the changes in X-ray dose guidelines over the years to modify this association. Given the developments in X-ray practices over the past 60 years that the authors allude to, it would be useful from a public health perspective to know whether the association is consistent across all time periods or is only limited to past practices.

Summary

This large population-based study allows for generalizable and precise estimation of the association between dental X-rays and meningioma, though it is difficult to rule out the possibility of bias (see below)

Despite the high number of statistical tests performed (which increases the chance of false positive results), the magnitude and direction of associations is generally consistent

Although the authors cite previous validation efforts claiming that biased recall of X-rays visits is minimal, this arguably remains a limitation of any case-control study like this one, given the tendency of people to overestimate previous exposure to explain their disease

The discussion does not go into sufficient depth to explain and interpret the results by, for example, contextualising them within X-ray practices over the last 60 years. The authors suggest an ‘apparent association’, and their recommendation to limit X-ray exposure infers causality, though they do not explicitly make this claim.

Conclusions

The authors are justified in suggesting an apparent association between X-ray exposure and the risk of meningioma. Their conclusions are generally supported by their results and analyses, but given the large number of tests performed, the potential for negative findings to be omitted, and the inherent biases associated with retrospective case-control studies like this, these results should be regarded as exploratory and ‘hypothesis generating’ rather than confirmatory and ‘hypothesis proving’.

Strengths/Limitations

Study design and analysis:

- (+) Case-control design is appropriate for this type of research question, given the relatively low incidence of meningioma in the population

- (+)The analytical method used in this study was appropriate for these data

- (+) Cases were frequency matched to controls by age, sex and state of residence

- (+) Results were adjusted for age, sex, race, education and history of head CT scans, but

- (-) they do not account for changes to X-ray doses over time that may have altered the observed associations. It may be unreasonable to assume the effect of exposure in one period is the same as the effect of exposure in another, i.e. that there is no ‘period effect’ (see glossary)

- (-) Case control studies like this can yield biased estimates of association due to (1) recall bias, (2) selection bias and (3) inability to control for all known and unknown confounders in the analysis

- (-) A large number of statistical tests were conducted, increasing the chance of false positive results

- (-) There was no analysis of the potential for non-participation to influence results. This may have introduced selection bias given the smaller proportion of controls who decided to participate (52%) than cases (65%); and the possibility that people’s exposure could influence their decision to participate

Discussion/Interpretation of results:

- (+) The conclusions are in line with the results and do not exaggerate findings, and findings generally agree with previous studies

- (+) The authors are upfront about acknowledging the issue of recall bias as a limitation

- (-) The discussion of results does not address:

- Why bitewing and Panorex, but not full mouth series, was associated with increased risk, given previous studies have found an association with full mouth series

- Whether the observed associations were consistent across time periods

- The WHO estimated lag time of several decades between exposure to ionizing radiation and meningioma disease – in other words, no distinction was made between recent exposure and exposure longer ago

Glossary

Case control study: a very practical design, but the evidence is lower than for most other study types (e.g. randomised trials or prospective cohort studies)

Recall bias: When the recollection of past exposure is different between cases and controls; typically when cases remember, and even exaggerate their recollection of, exposures more than controls

Selection bias: When the cases and/or controls are selected differentially on the basis of their exposure status, such that cases aren’t representative of all cases in the population and controls aren’t representative of the population that produced the cases

Period effect: When changes occur through time, such as the introduction of safer imaging technologies or medical treatments, that render comparisons across periods inappropriate without some form of adjustment

—————– —————– —————–

Before The Headlines is a service provided to the SMC by volunteer statisticians: members of the Royal Statistical Society and Statisticians in the Pharmaceutical Industry. A list of contributors, including affiliations, is available at http://www.sciencemediacentre.