Recommendations on greenhouse gases, water, solid waste, and transport were made last week by the Government’s Tax Working Group to help fund a transition to a more sustainable economy.

The Future of Tax report proposed the biggest changes to New Zealand’s tax system since the introduction of GST. Among the group’s many recommendations, including the introduction of a Capital Gains Tax, were a proposals to tax activities that have a negative effect on the environment.

The SMC has asked experts to comment on the environmental tax recommendations – please feel free to use these comments in your reporting.

Catherine Leining, Policy Fellow, Motu Economics and Public Policy Research, comments:

“The Government’s Tax Working Group (TWG) has recommended retaining the New Zealand Emissions Trading Scheme (NZ ETS) with reforms to provide greater guidance on price, generate revenue through auctioning, and enable periodic review. It also recommended extending emission pricing to biological emissions from the agriculture sector, whether through the NZ ETS or a complementary system. It suggested those changes can help drive behaviour change to reduce emissions, generate revenue supporting the transition to a more sustainable economy, and, in the longer term, broaden the overall tax base.

“New Zealand is facing a challenging low-emission transition and effective emission pricing needs to be part of the solution, alongside other regulations, policies and measures. It is positive the TGW recognises the merits of reforming rather than replacing the NZ ETS.

“As discussed further in a Motu paper, three practical design changes would enable the NZ ETS to send clear price signals for efficient low-emission investment: introducing auctioning under a cap which limits domestic emissions, adding mechanisms that guard against unacceptable price extremes in both directions, and applying both quality and quantity limits to purchasing of international emission reductions. Intended changes along these lines were announced by the Government in December 2018. Extending emission pricing to biological emissions, whether through the NZ ETS or other means, would help New Zealand to distribute mitigation effort and opportunities across sectors and enable more coherent price signals to guide land-use decisions.

“The TWG does not stray into the territory of recommending how ambitious domestic emission prices should be or assessing the potential fiscal effects from government purchase of international emission reductions to increase the volume of auctioning. While the TWG notes that accelerating the phase-out of free allocation would generate more auction revenue, it does not prescribe any conditions or rate for phase-out. This is an area for careful consideration as the potential risk and cost of emissions leakage overseas can be expected to decline under the Paris Agreement.

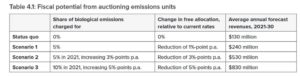

“The TWG’s estimates for NZ ETS revenue range from $130 to $830 million per year on average over 2021-2030, based on emission prices rising from $20 per tonne in 2021 to $50 per tonne in 2030. These scenarios align with the Government’s current carbon budget projections. This implies they leave a target deficit of 203 million tonnes of carbon dioxide equivalent to be achieved through domestic emission reductions, net forestry removals and purchasing of international emission reductions. The TWG notes that auction revenues would increase under higher target-consistent emission prices (e.g. up to $80 per tonne by 2030 as indicated in modelling applied by the Productivity Commission). In the long term, auction revenues will change in line with both higher emission prices and lower emissions under steeper targets.

“Building from the TWG’s recommendations, more work is needed on how the substantial revenue stream to be generated by the NZ ETS can be returned effectively to the economy in order to manage distributional effects from rising emission prices and support a smooth low-emission transition. More work is also needed on potential interactions between the NZ ETS, other environmental taxes (e.g. addressing waste, transport or water quality), and regulations. Above all, maintaining cross-party support for long-term policy continuity on the operation of the NZ ETS will be essential for sustaining confidence and investment by market participants as well as buy-in from the general public.

No conflicts of interest declared.

Associate Professor Ivan Diaz-Rainey, Co-Director of the Otago Energy Research Centre, University of Otago, comments:

“It is great to see environmental taxation so prominent in this report – it lays out immediate, medium-term and long-term objectives. The immediate category includes a strengthened NZ ETS so it is more like a tax (so this implies a price cap and perhaps a floor and critically more auctioning of allowances) and the inclusion of agriculture in the ETS or some complementary emissions pricing scheme.

“What the report shows is that by pricing agricultural emissions and auctioning more allowances, the NZ ETS could become a much bigger revenue generator. This is evident from figure 4.1 of the report (below).

“The status quo suggests annual revenues of about $130 million in 2021 from planned auctioning but if you charge for biological emissions to the tune of 10 per cent in 2021 and reduce free allocation of units under the ETS by 5 per cent yearly, then that figure jumps to closer to $830 million. This then becomes a material tax take but still needs to be put into context of the total tax take of some $75 billion annually. Probably not enough to start to deliver the ‘double dividend’ I discuss below.

“In terms of the medium term, there is talk of revenue recycling which sounds distinctly like hypothecation of a tax (where tax revenues from a specific tax are ring-fenced for particular expenditure); treasury departments around the world do not like it as they like to aggregate tax revenues and direct them where the need is greatest. But in terms of legitimacy and communication of new taxes this does have its appeal, even if Treasury wonks will tell you it makes no sense.

“Perhaps unsurprisingly, the long term objective, of having environmental taxes become a much more significant part of the tax base, is more vague and aspirational. But this is a bit of a shame. Environmental economists have suggested that there is a ‘double dividend’ from such taxes; namely 1) we improve the environment, 2) the money raised can be used to cut other taxes that are distortionary. Tax bad things (pollution) so you do not have to tax good things (employment) – so perhaps greater environmental taxes could lead for instance to a UK type tax free personal allowance (e.g. first $20,000 free from tax) thereby mitigating any regressive aspect of the environmental taxation and providing strong incentive for those outside the workforce to enter or improve the lot of low income citizens? This ‘take and give’ is going to be essential if environmental taxation is not going to have a serious backlash as it tends to be regressive (tends to affect low and middle income families more). We do not want a kiwi version of gilets jaunes.

“Another interesting thing to watch over the coming months and years is the balance that the government strikes between incentives (broadly taxation) and regulation. The former are good at altering behaviours but sometimes taxes are not enough and regulations are needed.

A classic case is rental housing quality where taxes will have slow and muted effect due to what economist call split incentives (why would landlords make homes more energy efficient at their cost when they don’t pay the energy bill?). So in this respect, I really welcome the Government announcement on this issue which sets minimum standards of rental household insulation. It feels like there is finally some walk with the talk.”

No conflicts of interest declared.

Dr Carwyn Jones, Senior Lecturer, Faculty of Law, Victoria University, comments:

“The precise nature of Māori rights and interests in fresh water is the subject of some dispute.

“The Waitangi Tribunal is currently completing the National Fresh Water and Geothermal Resources inquiry, which addresses the nature of Māori rights to water. The Tribunal issued an interim report on the first stage of this inquiry in 2012. In that report, the Tribunal found:

that Māori had rights and interests in their water bodies for which the closest English equivalent in 1840 was ownership rights, and that such rights were confirmed, guaranteed, and protected by the Treaty of Waitangi, save to the extent that there was an expectation in the Treaty that the waters would be shared with the incoming settlers.

“The Tribunal determined that such rights:

included authority and control over access to the resource and use of the resource. This authority was sourced in tikanga and carried with it kaitiaki [guardianship] obligations to care for and protect the resource. Sometimes, authority and use were shared between hapū but it was always exclusive to specific kin groups; access and use for outsiders required permissions (and often payment of a traditional kind).

“In the course of the National Fresh Water inquiry, Māori have asserted that rights deriving from tikanga Māori, the common law doctrine of aboriginal title, and the guarantees in Te Tiriti o Waitangi, include rights to:

a) possess, occupy, use and enjoy their waterways;

b) make decisions about the use of their waterways;

c) access to their waterways;

d) control access to their waterways by others;

e) use and enjoy the resources of their waterways;

f) control the use of their resources by others;

g) trade in those resources;

h) control the taking of their resources by others;

i) maintain and protect important cultural sites; and

j) maintain, protect, and prevent the misuse of cultural knowledge.

“The Crown acknowledges that Māori have rights and interests in freshwater but maintains that no one owns freshwater. The Crown’s position is that the content of Māori rights to water is primarily directed at use and control and that such rights can be recognised via regulation and/or co-governance arrangements.

“Some Māori parties have contended that these parameters that have been set by the Crown are preventing an exploration of the full range of options that might provide for the most appropriate recognition of Māori rights.”

Conflict of interest statement: I peer-reviewed a report entitled ‘Ngā Wai o the Māori: Ngā Tikanga me Ngā Ture Roia – The Waters of the Māori: Māori Law and State Law’ which was prepared for the New Zealand Māori Council and submitted in evidence in the Waitangi Tribunal’s National Fresh Water inquiry.

Dr Viktoria Kahui, Senior Lecturer, Department of Economics, University of Otago, comments:

“The Tax Working Group (TWG) notes that water taxes will need to take account of Maori rights and interests, but no information is provided as to how other than ‘through the Waitangi Tribunal and discussions between the Crown and iwi/Māori’.

“Water abstraction is a challenging issue, as noted by the TWG, as it involves many stakeholders and the long-standing issue of ownership. Who exactly owns the freshwater in New Zealand? Under the Treaty of Waitangi, Māori have a legitimate claim to its ‘exclusive and undisturbed possession’, providing a case for a share in abstraction revenues and preferential access. But it is also water quality that matters to Māori, and society at large. Fertilizer taxes are one way to address New Zealand’s pollution problem from dairying, but the pressures on both water quantity and quality are a complex set of changing dynamics, which are hard to project into the future.

“A recent bill that passed the Whanganui River Claims Settlement in 2017 by granting the Whanganui River legal personhood status has been a ground-breaking example of bypassing the issue of ownership by granting legal personhood to a natural entity. The bill establishes the river as ‘an indivisible and living whole comprising the Whanganui River from the mountains to the sea, incorporating all its physical and metaphysical elements’. This reconceptualisation of the meaning of legal personhood allows the enactment of the Maori worldview within the existing and any future regulatory framework that may include the adoption of water tax instruments. It is not so long ago that a corporation retaining legal status as a person was unthinkable. Freshwater lakes, rivers and aquifers as legal entities should now be on the TWG’s radar.

No conflicts declared.