This week I had the pleasure of attending part of a University of Otago symposium on infectious diseases and gave a short talk on the role the media can play in communicating risk and uncertainty in times of crisis.

It was a fascinating afternoon, capped off with an excellent public lecture by visiting expert Professor David Heymann covering the decades of work undertaken to identify Ebola, treat its victims and stop its spread.

Professor Heymann’s message was clear – while development of a vaccine for Ebola is a welcome development, what has killed a lot of Ebola victims and exacerbated the spread of the disease is poor hospital processes.

In other words, its the simple stuff that gets you in trouble, like getting too close to patients who might be infected, or not properly sterilising needles. If you get the basic hygiene right, you can limit the spread of infection. Unfortunately, the places prone to Ebola outbreaks often have inadequate medical infrastructure and processes.

Good hygiene essential

The same thing basically goes for communicating science during crises, like an Ebola outbreak. The better prepared you are up front, the clearer your key messages are and the more confident your people are in communicating, the less likely fear, uncertainty and misinformation about an outbreak is likely to spread via the media.

The mainstream media has an important role to play when experts want to communicate risk and uncertainty. But the media is also in a state of flux, poorly resourced and increasingly lacking health and science specialists. Social media allows everyone to express an opinion and the evidence increasingly shows that people are most influenced by others in their social network, so what other people say informally is as or more important than expert opinion (see BREXIT and the alleged backlash against experts).

My message to the symposium therefore, was that experts need to step up and get better ‘hygiene’ into their science communication practices to help the media do a good job of covering these issues when the public most needs health-related information.

Download or order free copies of the SMC’s Desk Guide for Scientists: Working with Media.

Harnessing the hype

Below are some excerpts from my slides Harnessing the Hype, which I showed at the event.

From Ebola to the AIDS/HIV pandemic to SARS and avian flu, infectious diseases are and have always been prone to hype. It is easy to see why. When the media is confronted with an emerging disease that scientists don’t fully understand, one that has nasty symptoms and is potentially fatal and has the potential to spread globally quickly, the media is going to go big on the story.

So an element of hype upfront is inevitable.

But stories evolve. We saw with the 2009 N1H1 outbreak the various stages that story evolved through – from the initial alarm around a new strain of flu for which there was no vaccine, to the realisation that younger and seemingly healthy people were being struck down by it, to the development of a vaccine, to the criticism that health bodies and vaccine companies over-reacted in their response to the swine flu outbreak.

How experts communicate can influence or even prompt each evolution – and help prevent unhelpful mutations of the message. Communicating risk and uncertainty relating to public health is as tough as it gets – the stakes couldn’t be higher.

The media, with its insatiable hunger for clicks and eyeballs is more likely to hype an emerging infectious diseases story than ever before. But that hype can be harnessed by media savvy experts and their advisors.

Outbreaks hog the headlines

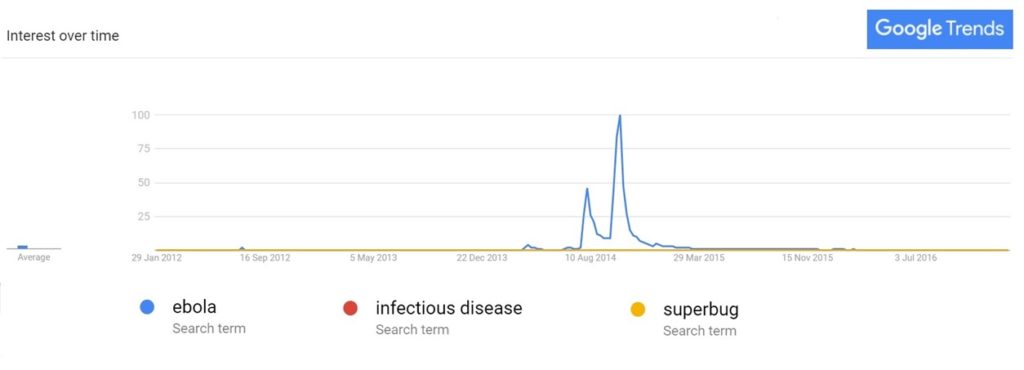

Coverage of infectious diseases is spiky. Despite all the advocacy around pandemic planning and thoughtful commentary on the rise of antimicrobial resistance, it is the sudden new and scary diseases that capture interest, as this Google Trends graph well illustrates.

So when the spike happens, it is crucial for experts to be ready with clear messages about risk and uncertainty and what actions they want from the public. They need to ride that interest and adapt the message as the story evolves. They need to quickly correct misinformation and the better relationships they have fostered with the media in ‘peace time’, the better their ability to do that.

While the tent pole events that disease outbreaks represent grab the bulk of the public’s attention, infectious diseases also still need to do the hard yards informing and, yes, educating the public about infectious diseases. That’s because when we are confronted with alarming headlines about a deadly pandemic raging out of control, we are much more likely to be able to deal with the ‘mental noise’ that creates if we have a ‘mental model’ for how diseases and the methods of tackling them work.

Finally, the infectious diseases expert community needs to do more to engage hard to reach audiences – where geography, culture, religion and even anti-vaccine sentiment limit the willingness of a group of people to take action to limit the spread of disease. This is the hardest task of all, but the groundwork that will pay off most handsomely when the next infectious diseases story goes viral…

Five tips for communicating risk and uncertainty.

1. Have multiple consistent and accurate messages

DON’T be responsible for the hype yourself

DO be specific – ‘what, when, how, and for how long’

DO tailor the messages to the audience

DO pre-test messages with diverse audiences

2. The vacuum will be filled… make sure it is by you

DON’T hope that interest will fade quickly

DON’T overload journalists with detail

DO respond quickly to media queries

DO outline uncertainty and limits of knowledge

3. Be proactive in correcting misinformation

DON’T automatically blame journalists for inaccuracies

DO request corrections quickly

DO adjust key messages if necessary

DO look for follow-up media opportunities

4. The public has a voice – listen to it!

DON’T bombard the public with more facts

DO accept their concerns, even if they are irrational

DO look for opportunities to engage directly

DO correct misinformation on social networks

5. Build science communication capability in peace time

DON’T wait until need for information spikes

DO take time to foster media relationships

DO develop your science and risk communication skills

DO take time to work with hard to reach audiences

Resources:

Check out the excellent new book Risk Communication and Infectious Diseases In An Age of Digital Media (2017)

Literature review on effective risk communication – from the European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control. (2013)

Eurosurvellience: Risk Communication as a Core Public Health Competence in Infectious Disease Management. (2016)