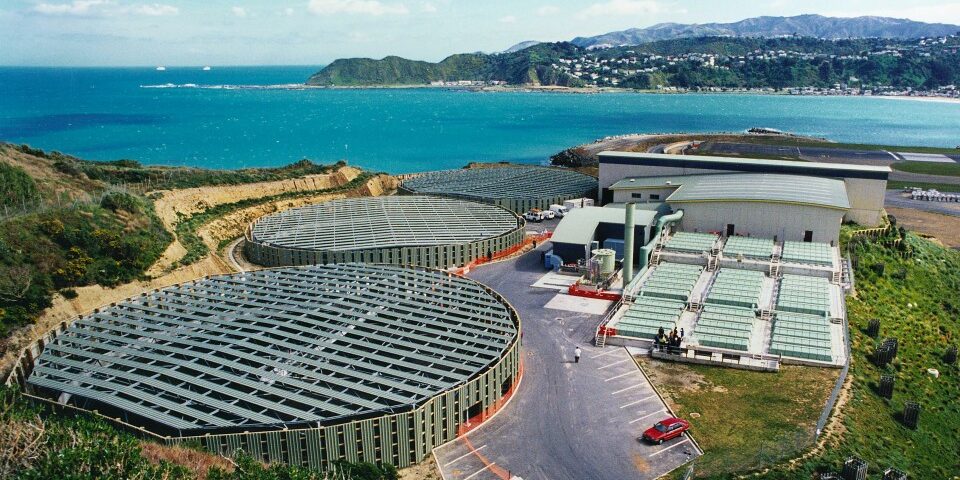

Health officials are warning people to stay off Wellington’s south coast beaches, due to the infection risks from the Moa Point wastewater plant failure.

With untreated wastewater still being pumped into the Cook Strait, people are also being warned not to eat kaimoana from the area, and to avoid contact with sea spray.

Meanwhile crews trying to clear and repair the plant may have to wear breathing gear to avoid inhaling dangerous gases.

The SMC asked health experts to comment. Previous comments from wastewater and environment experts are available on our website.

Dr Nick Kim, Senior Lecturer in Applied Environmental Chemistry, School of Health Sciences, Massey University, comments:

“I’ve heard this referred to as an ‘environmental disaster’, and that’s about correct.

“From my understanding, there is a priority on trying to clear the flooded treatment station before things ‘go anaerobic’. At the plant there will be microbes eating up the readily available organic matter, and they, much like us, use oxygen up and produce carbon dioxide. Once there’s not enough oxygen, they die off, so the anaerobic microbes take over. These are the bacteria that can live in the absence of oxygen, and they can produce toxic gases – in particular hydrogen sulfide and other volatile organic sulfur compounds. Most of these sulfur gases have strong odours.

“If that happens, you’ll have similar problems as at the wastewater treatment plant in Bromley, Christchurch. Elevated hydrogen sulfide inside the plant would be directly hazardous to workers. The significance of possible exposures of nearby residents would also need to be considered and – depending on specifics – there may be a need for air quality monitoring. So ideally, we won’t go there.

“Offshore, in the seawater, there’s no question that recreational limits for total coliform bacteria, and E.coli, will be being exceeded, across wide areas and at various times. These tests are mostly used as indicators that other pathogens could be present – with total coliforms as the preferred indicator for marine waters. If you were to swim in a plume or a diluted plume, you’d have a pretty high chance of picking something up. I would not be swimming there.”

Conflict of interest statement: “None.”

Associate Professor Barry Palmer, School of Health Sciences, Massey University, comments:

“One of the problems here is that a large number of microbes are entering the marine water. Many of them will die once they hit that environment, but some, including some human pathogens, can survive for quite a number of days, up to weeks. In general there will be a risk to human health until the discharge stops.

“In standard water quality testing, marine waters are tested for a group of bacteria called enterococci. In some circumstances tests for total coliforms and E.coli are also performed. The principle here is you’re testing for an indicator organism, which are found in the human gut and survive in wastewater for days or weeks. They’re not necessarily pathogens in and of themselves, but they’re indicators of pathogens, because to find the disease-causing organisms in that environment is like looking for a needle in a haystack, so you might well miss them. Generally, the standard test is to take 100 millilitres of water and then through some microbial growth testing which takes around 24 hours, you’re able to see what numbers are present there.

“For swimming, probably the Kapiti Coast, at least, is where I’d be heading, not in any of the harbor beaches. They may be perfectly safe, but tidal flows are going to bring some of that contaminated water into the harbor, and then suck it out again. The LAWA site shows which beaches in the area are safe to swim in.

“Changes to wastewater regulations in December mean that wastewater treatment plants in some circumstances now have higher limits – so there they can discharge more wastewater, in some instances than they were able to before. The bottom line is, there might well be more wastewater going into water body environments in future than there has been.”

Notes: “I coordinate a Massey University course called Epidemiology and Communicable Diseases and teach in another course called Environmental Monitoring. One of the things we cover in both is water quality testing – the type of testing that Wellington Water is doing from the beach to get an idea of how bad water quality is.”

Conflict of interest statement: “I am a part owner of the company Liquid Systems (2009) Ltd, that consults to the NZ waste industry.”