There is now a strong likelihood that measles is spreading through communities, according to Health New Zealand.

Unlike other measles cases reported recently, two new cases in Manawatū and one in Nelson have no connections to international travel, suggesting that the highly contagious disease is now spreading between people within Aotearoa.

The Science Media Centre asked experts to comment on what this could mean for communities in NZ.

Dr Natalie Netzler, Senior Lecturer, Faculty of Medical and Health Sciences, University of Auckland, comments:

“The impacts of measles can be underestimated within the community. Measles infection causes a type of ‘immune amnesia’ that erases our immune system’s memory of previous infections. This virus can also cause a range of serious complications ranging from pneumonia, hearing loss, through to serious inflammation of the brain, and death. In rare cases it causes a progressive, fatal neurologic disorder that can appear many years after infection.

“It’s important for our communities to know that there are no specific antiviral treatments for measles infection and the best way to avoid these complications is through two doses of the MMR immunisation.

“To help us to protect all those individuals that can’t be immunised because they are too young (under 12 months), or too unwell, it’s important that we get our MMR immunisation rate as high as possible throughout the community to prevent others passing it on to these vulnerable people.”

Conflict of interest statement: “I work with several Pacific and Māori organisations and health providers to support our communities to make informed decisions on immunisation.”

Dr Chris Puli’uvea, Immunology Lecturer, Biomedicine & Medical diagnostics, AUT, comments:

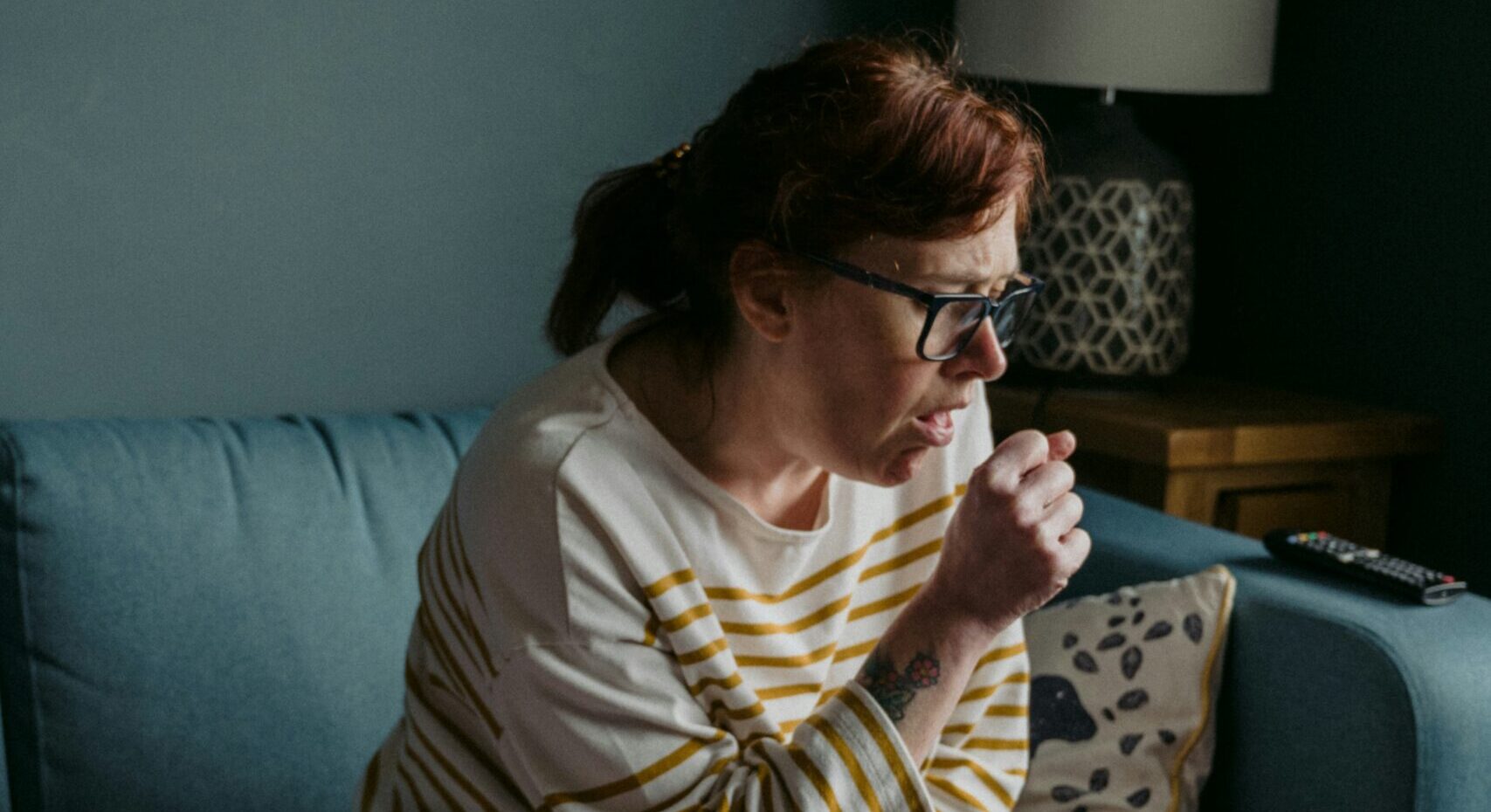

“The measles virus is highly contagious and can be spread in the air by someone who has been infected, either by talking or coughing. This virus can remain in the air for up to 2 hours, thereby increasing the chances of infecting others in the surrounding. Our immune system can put up a fight; however, the measles virus can infect these specialized cells, much like a Trojan horse, and suppress our immune system, leading to secondary infections.

“Measles infection can also cause immune memory loss when the measles virus hijacks our immune memory cells and kills them. This is one of many long-term issues associated with measles infection, as immune memory is the immune system’s ability to remember previous infections. Having immune memory means your immune system can mount a quick and effective attack on the threat if you encounter it again in the future, protecting you from getting very sick and needing hospital care. This ability can be lost after getting measles.

“I strongly urge our Māori and Pacific communities to double-check our whānau/fanau are fully protected by contacting your family doctor to make sure. Being fully vaccinated is our best protection against this threat, to ensure a healthy future for our tamariki.”

No conflicts of interest.

Professor Sir Collin Tukuitonga, director of Te Poutoko Ora a Kiwa – Centre for Pacific and Global Health, University of Auckland, comments:

“Pacific and Māori New Zealanders have particularly low vaccination rates, putting them at greater risk during the current outbreak.

“In December 2024, only 70.4 percent of Pacific two-year-olds in New Zealand and 63.3 percent of Māori toddlers were vaccinated against measles, and just 76.4 percent of all two-year-olds in New Zealand.

“That rate isn’t enough to offer protection to the group.

“Measles is a fairly vicious disease – one in three children who catch it end up in hospital and some will have severe brain damage.

“So right now when the risk is elevated, it’s important for Māori and Pacific families to make sure their babies and children are vaccinated, because children aged under five are most vulnerable.

“People aged over 55 who were born in remote Pacific Islands could also be at risk, so they should check with their GP whether they need to be vaccinated against measles.

“The vaccine is usually given when a child is 12 to 15 months old, but it’s never to late to get vaccinated against measles. Families should also ask their GP whether younger babies should be vaccinated earlier, if their circumstances put them at risk.”

No conflicts of interest declared.

Dr Nikki Turner, Principal Medical Advisor, Immunisation Advisory Centre, comments:

“A surge in measles cases worldwide combined with increased international travel means New Zealand is always one plane ride away from the disease being introduced here. But while we can’t prevent measles being introduced, we can – and should – stop community transmission.

“Vaccination is key. Because measles spreads so quickly, ensuring high vaccination rates evenly across communities is critical to preventing outbreaks. Coverage of 95 per cent or greater with two doses of measles-containing vaccine is needed to protect communities. If we have patches of low coverage, that is how the virus will spread.

“It’s really important for children from 12 months of age, and adults who were born after 1969, to be up-to-date with two doses of the measles, mumps and rubella (MMR) vaccine. Immunisations are free for most and two doses of MMR vaccine are 99 percent effective. Measles is a hideous disease. We want everyone to be protected. With measles cases rising across the motu, our advice is don’t wait – vaccinate.

“We applaud the response by health authorities and communities in Northland after the first measles cases were confirmed in the region last month – great contact tracing, isolation and huge efforts to get people immunised have helped to stop the spread. Vaccination is so vital, and the message is important for all individuals and communities – let’s look out for each other.”

No conflicts of interest.

Dr Helen Petousis-Harris, Associate Professor, University of Auckland, comments:

“Measles is one of the most contagious viruses known to humanity — if it’s in the community, it spreads like wildfire among the unvaccinated. What we’re seeing now is the predictable consequence of years of slipping immunisation coverage in Aotearoa New Zealand and a resurgence overseas. This disease can be very serious with long-lasting consequences.

“National childhood vaccination rates have fallen well below the 95% threshold needed to stop measles transmission. Some communities are sitting dangerously low, even well below 70%. These are tinderboxes for outbreaks — once measles enters, it spreads rapidly and hits the most vulnerable hardest: babies, children, and those with weakened immunity. In the last NZ outbreak, there were over 2100 cases confirmed and 765 hospitalisations. Since this time around 370,000 more babies have been born in Aotearoa, and based on measles vaccination (MMR) coverage over this period, around 170,000 are probably vulnerable to measles infection.

“Measles has a sting in its tail. Many people do not realise that the measles virus infects and destroys memory B and T cells, wiping out years of acquired immunity to other pathogens. Recovery requires re-exposure to common microbes to rebuild immune memory — which happens faster in adults, but more slowly in children, leaving them vulnerable to secondary infections for months to years. Subacute sclerosing panencephalitis (SSPE) is a rare but always fatal degenerative brain disease that can appear years after measles infection—typically 5–10 years later. It is caused by persistent measles virus in the brain and occurs almost exclusively in those who caught measles before age 2. The risk is estimated to be around 1/600 cases.

“Globally, measles has surged back. It was rising before the pandemic, then jumped after immunisation programmes were disrupted. We have seen major outbreaks across the Pacific, Asia, and Africa and now more recently, the United States and Canada. New Zealand isn’t immune to that trend — we have effectively lowered our defences to imported cases. Essentially, we are being constantly peppered with new cases, and this will continue for the foreseeable future. What we can do is ensure we have enough community immunity to stop further spread.

“Every case of measles is a failure of prevention. The vaccine is very safe, free, and incredibly effective. Measles will exploit every gap we leave.”

Conflict of interest statement: “HPH has received research funding from industry for investigator led projects, served on expert advisory boards for industry, WHO, NZ government, and on clinical trial DSMBs. She is co-director of the Global Vaccine Data network who are conducting safety studies on COVID-19 vaccines across over 30 countries.”

Professor Michael Plank, School of Mathematics and Statistics, University of Canterbury, comments:

“It is unfortunately not surprising that measles appears to be spreading in the community because childhood vaccination rates have fallen dangerously low. Measles is highly contagious: if nobody had any immunity, a person infected with measles would pass the virus onto an average of around 15 other people. That means that at least 14 out of every 15 people (around 95%) need to be immunised to prevent measles outbreaks. Sadly vaccination rates have fallen well below this, which allows measles to spread.

“Vaccination rates are not evenly distributed and communities with below average rates will be particularly vulnerable to large outbreaks of measles, which will have extremely damaging health impacts.

“The MMR vaccine is highly effective at preventing measles. Contact tracing and quarantine measures will help contain outbreaks, but the only sure fire way to stop measles from spreading in the long term is to lift vaccination rates.”

No conflicts of interest.

Professor Michael Baker, Department of Public Health, University of Otago, Wellington, comments:

“Last year we published an extensive Expert Briefing “Urgent action needed to prevent a measles epidemic in Aotearoa New Zealand.”

“This Briefing included a section on ‘Measures to better manage measles outbreaks and epidemic spread when these occur’. These points are all still valid in the current situation where measles appears to be spreading in the community.”

No conflicts of interest.