MethaneSAT lost contact with the ground on Friday 20 June, and mission operations learned today that it has also lost power.

MethaneSAT said in May that increased solar activity had been sending the satellite into ‘safe mode’.

The satellite was launched last March to track methane emissions from oil and gas. It is New Zealand’s first official space mission—the government contributed $29 million to the satellite, which is primarily funded by a US-based nonprofit.

Earth Sciences New Zealand (formerly NIWA) has published a statement on MethaneSAT’s agricultural research programme. The University of Auckland’s Mission Operations Control Centre was due to take over mission control. A statement from the university is available here.

The SMC asked experts to comment.

Associate Professor Nicholas Rattenbury, Department of Physics, University of Auckland, comments:

“MethaneSat is reported to be defunct. This is disappointing, of course, for everyone on the mission development, operations, scientific and engineering teams. Having been in that position personally, I sympathise. That a spacecraft fails on orbit is not surprising. The space environment is unforgiving. Broken things in orbit tend to stay broken. In some cases, workarounds can be found, and the space industry has many examples of extraordinary engineering feats accomplished to bring a stricken spacecraft back towards full functionality. However, it appears that MethaneSat is unrecoverable. Space, as they say in the industry, is hard.

“New Zealand taxpayers gave $29m to MethaneSat. The intended aim was growing the NZ space industry. This would be accomplished through gaining experience in operating a satellite at The University of Auckland’s Te Pūnaha Ātea – Space Institute and through research led by a NIWA scientist on how to use MethaneSat to measure agricultural sources of methane. But with this recent announcement it looks like these benefits will be limited, at best.

“Even though it appears that New Zealand was not likely involved in the chain of events leading to the underperformance of MethaneSat, we as investors in the project are entitled to an explanation.

“The technical issues encountered by MethaneSat are not a concern here for NZ – we didn’t build MethaneSat. However, there is a question of whether or not we should have taken a closer look “under the hood” before investing in MethaneSat. The principle of caveat emptor is true for spacecraft as much as it is for purchasing a car. While we were not involved in the MethaneSat mission design, satellite construction and testing, we were certainly entitled to such relevant information so we could make a fully informed decision on whether or not to invest. A question, then: Who on behalf of the NZ taxpayer was asking these and similar questions prior to our investment and how were the answers used in the decision-making process?

“New Zealand has scientists and engineers working at public-funded universities that can contribute to future decision-making processes for the next space mission supported by the New Zealand taxpayer. During the MethaneSat post-mortem, a question that could reasonably be asked is to what extent these experts were consulted during the decision-making process to invest in MethaneSat. What lessons here could be learned to inform the next process through which we as a nation invest in a future space mission? When questions were being asked about the health of MethaneSat, to what extent are we, as investors, happy with the explanation that much information was veiled owing to reported obligations of confidentiality or commercial sensitivity?

“I work towards fostering the New Zealand space sector, especially in the areas where we can push back the boundaries of human knowledge via the safe, peaceful and sustainable use of space. Space is hard, unforgiving, expensive and frustrating. It can also be rewarding, and this is part of the excitement that I see reflected in the students I teach. For a nation with ambitions to utilise space for science, technological development and commercial gain we also have to acknowledge that failure is a part of that journey. To make the best use of our very limited resources, we owe it to ourselves to examine our processes in the fullest light of disclosure and by leveraging all available expertise.”

Conflict of interest statement: “I am not associated with MethaneSAT in any way. These views are not necessarily those held by The University of Auckland.”

Professor Richard Easther, Department of Physics, University of Auckland, comments:

“First and foremost, this is a tragedy for the people here who worked hard on it, and for New Zealand science.

“However, it is important to remember that a key justification for us getting involved with MethaneSAT was to “build capacity” to operate in space as a country and we can still get a return on our investment by learning from this loss.

“I was excited when we got involved in 2019, but MethaneSAT was years late launching and kept pumping out upbeat comms even after it became clear that the spacecraft had major problems.

“As a country we need a “no blame” review to understand how New Zealand blew past so many red flags about MethaneSAT’s operation. Rocket Lab’s success creates a remarkable platform for New Zealand to do low-cost, globally significant space missions and our involvement with MethaneSAT has squandered that opportunity.

“However, if the best time to start would have been 2019, the second best is tomorrow – the opportunity is still there.

“But without getting ahead of the post mortem it is clear that we need to make better decisions about strategy and that will only happen if expertise in the science community is fully engaged from the outset.”

Professor Craig Rodger, Beverly Professor of Physics, University of Otago, comments:

Note: Professor Rodger is an expert in solar weather.

Are satellites often ‘lost’?

“Satellites do go into safe mode and need to be reset. Satellites are also sometimes lost – for example, there is internal damage which triggers them going into safe mode but they never come back and just stop talking to you. But that sort of thing is pretty damn rare.

“When satellite operators talk about ‘safe mode’, that’s usually in the context of impacts triggered by the satellite being bombarded by hot protons and hot electrons. When they are around, it’s a tough environment to put your spacecraft in. The thing that surprises me is that the space environment was relatively benign around the 20th of June (when they lost contact with MethaneSAT), and had been for a few weeks. I’m not saying it was dead quiet, but it was sort-of background level conditions – especially for this time in the 11 year solar cycle where the sun is restless in a big way, and when we expect the environment to be a bit challenging.”

How can solar weather affect satellites?

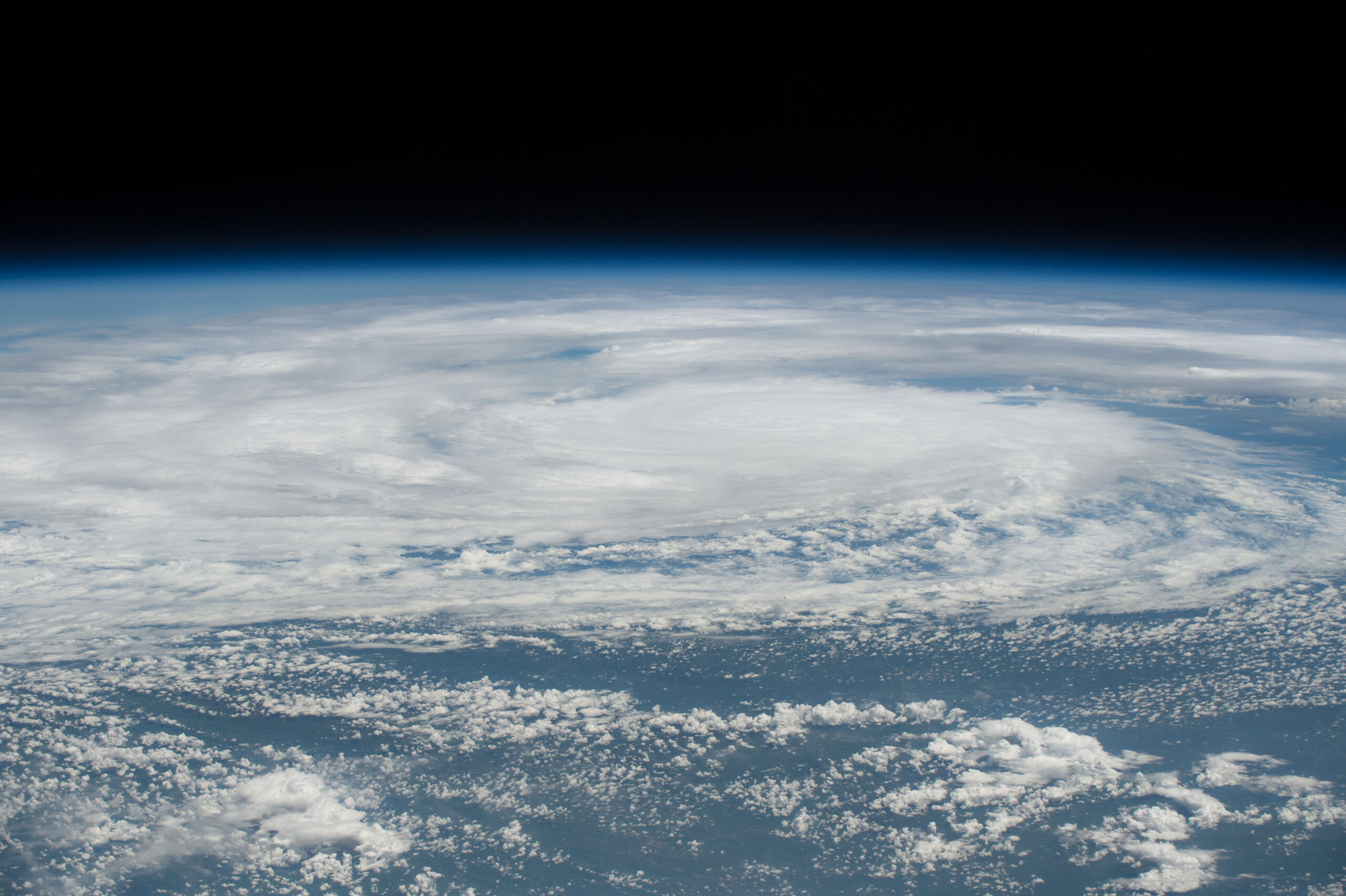

“There have been moments when it’s been interesting in the last year and a bit, but there have not been extreme conditions in the space environment. In that time there was some unusually cool stuff in terms of the atmosphere – you may have seen the aurora in May or October last year – and also geomagnetic storms. However, that activity wasn’t linked to events making a horrible space environment. It’s like weather: we aren’t talking about something extreme like ‘Cyclone Gabrielle’, we’re talking about normal slightly active conditions where ‘some storms have come through’. Typically people build their equipment to handle that. We haven’t had something like Cyclone Gabrielle in the space environment for about 20 years, in terms of radiation doses. So it’s puzzling, what has happened here with MethaneSAT.

Is this a concern for other satellites?

“One thing that has been talked about for a while now is that during the last solar maximum, roughly 11 years ago, it was unusually benign. So if you are a spacecraft engineer who has grown up in an environment where everything is pretty quiet, there’s a worry you will build for conditions that have been like that for your entire life. This would ignore the fact that 20 or 30 years ago we made measurements in space that were like ‘holy crap what’s going on right now?’ The satellites back then had bad days, but were well built. The new space industry has developed in very quiet conditions, and now we’re moving into more normal times, and if you’re not ready for that normal background level of space weather, that’s a potential problem.

“But we are not hearing internationally of lots of spacecraft just dropping dead. Maybe some people have got a particularly fascinating design with certain issues and sensitivities, but we are not constantly hearing about how the enhanced solar activity is causing many satellites to have major problems. I’m not saying there’s zero issues, we have some, but this isn’t an incredible big deal across the world for other satellite operators.

“There are a lot of satellites nowadays made by students in universities as a learning experience – there are a very large number of those which are referred to as ‘dead on arrival’, or ‘DoA’. They never survive launch or don’t turn on when they get to orbit. It used to be that more than half of student satellites were ‘dead on arrival’, but as people get their act together, that number is going down. That issue is linked to a very specific satellite manufacturing sub-environment where you don’t have experienced engineers – it’s all about learning, whereas I hope that the people who designed MethaneSAT had a lot of knowledge about spacecraft design and the environment it was going into.

“Now, I’ve never designed a satellite – it would be ‘dead on arrival’ if I built a satellite. But I do watch the satellite environment and the information from the NOAA Space Weather Prediction Center in the US and so I have an idea of the ranges of activity that occur – what quiet looks like, what disturbed looks like, what ‘big arse holy crap’ looks like. Conditions have not been really active, but MethaneSAT seems to be having a bad time for quite a while now.

“The other thing that can happen is that you just get unlucky in terms of space environment and you happen to fly through something – your hardware triggers and you go into safe mode. But that’s like winning the Lotto. From what we’ve been told in the media, it sounds like this has happened to MethaneSat multiple times. These guys are apparently being repeatedly unlucky, and that’s weird. That would happen if you have something fundamentally wrong with the design of your spacecraft – but it’s hard to suggest anything definitive because the information that’s been provided, while it uses technical and meaningful words, doesn’t give enough detail to link it to what’s really been happening.”

No conflicts of interest.