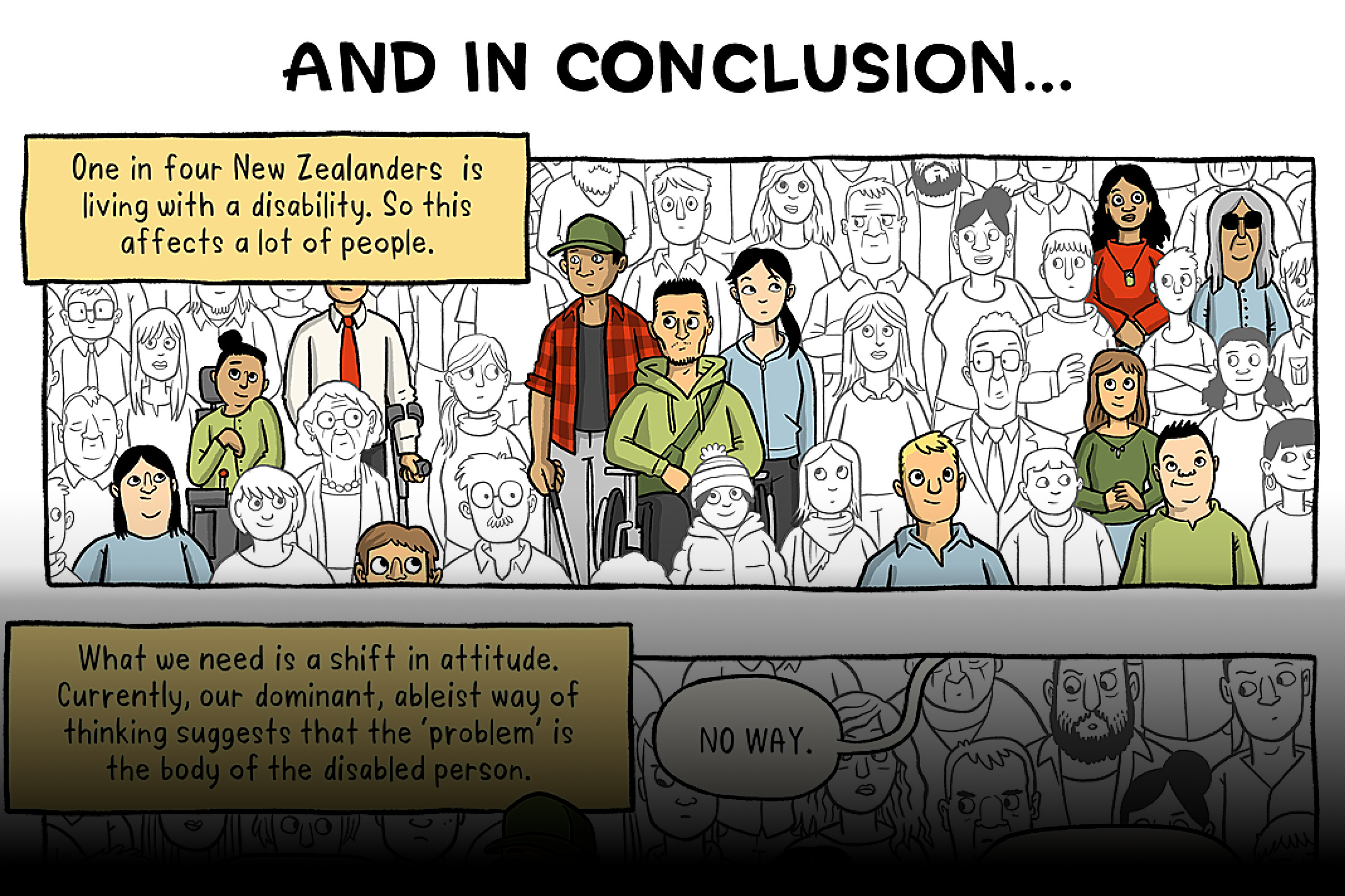

After finishing a study on everyday ableism, a team of researchers at Massey University decided to commission illustrator Toby Morris to present their results as a comic strip.

The researchers have now written a paper about the creative collaboration. They point out struggles, like balancing creative impact with staying true to the data. However they say the comic helped make their findings understandable to the general public, which in turn helped drive social change.

The SMC asked experts to comment on how visuals can be used to communicate science.

Professor Karen Witten, SHORE and Whariki Research Centre, Massey University; and co-author of the paper, comments:

“The comic developed a life of its own as it was so easily shared digitally. The research team began the process by asking for it to be circulated to schools through the Education gazette and a newsletter to school governance board members. Several government Ministries uploaded it on their websites, community groups circulated it to members, and it was picked up by online news outlets after an article in The Conversation. We also printed posters of the comic and teachers requested copies to display in their classrooms and to use as a human rights teaching resource.

“I think it was picked up widely for several reasons. The vignettes depicted shocking truths that were grounded in disabled young people’s stories of their everyday experiences of the discrimination and stigmatisation of ableism. Toby Morris’s illustrations are brilliant and very appealing, and the messaging had been finely honed in a co-design process involving Toby, the research team, and disabled young people.”

Conflict of interest: Karen is a co-author of the research.

Gabby O’Connor, artist-researcher, Sustainable Seas National Science Challenge, comments:

“These results are no surprise – it’s become increasingly clear in public debates about hot topics like climate change and anti-vaccination that facts alone do not change hearts and minds, and that many peoples’ memory recall is in images not lists of information. We ‘construct’ knowledge from many sources, so using a well-planned combination of methods is more effective. Using narrative story-telling in combination with visual sources is even more so.

“Images support text, but are also a form of text. Not everyone has the same levels of literacy, so images can provide an entry point to new information that is more inclusive. Images can also provide meaningful context to the message. The result allows for empathy, memory and imagination (imagining other possible scenarios, problem solving), and connecting to culture and values.

“My research findings show that between 96–100% of those who participated in our art-science-education workshops for The Unseen (a collaborative community artwork inspired by marine science) recalled science information afterwards. I attribute this to the research providing multiple entry points and modes of learning that cover visual, aural, physical, mnemonic, sensory, experiential forms of knowledge and stimulus.

No conflict of interest.

Dr Ciléin Kearns, Medical Illustrator and Senior Clinical Research Fellow at the Medical Research Institute of New Zealand / Artibiotics, comments:

“This paper presents a behind-the-scenes look at something that is rare and powerful in the world of research; a truly collaborative research effort between scientists and participants of their studies. Our volunteers are the people who make our research possible, and whom it should ultimately serve. Most research is published into ivory towers of academic prose, coded in scientific language, and often locked behind paywalls. This gets in the way of progress; for science to achieve its potential impact it needs to be easy to read and understand – many of our greatest advances have come from the pollination of ideas from people far removed from our fields.

“From my experience in clinical research, although we offer to share summaries of research with participants, there is little guidance on the form this should take, or research on what mediums are preferred. This is something I’ve been actively investigating with my own work creating comics and other visual media to make medical research more accessible, and the results have been largely supportive of comics so far.

“Dr Calder-Dawe and her team involved an illustrator, Toby Morris, to help translate their academic findings into a comic which was designed with input from their participants. Comics weave images and text together into stories that can communicate more than the sum of their parts. Throughout the COVID-19 pandemic we have seen how effective they can be with notable examples including Dr Siouxsie Wiles and Toby Morris’s collaborations in New Zealand to share pandemic science in animated comics. We can see growing global recognition of the role these can have for important health issues in the World Health Organisation’s endorsement through sharing many of these comics, and supporting translation efforts on projects like The COVID-19 Chronicles comedy/expert opinion comics from National University Singapore Yong Loo Lin School of Medicine.

“In a country that is increasingly recognising how our systems are built to cater to majority groups, and often exclude those most in need; it’s timely to truly involve participants in research that serves them and their communities, and to find creative solutions to maximise the impact of these efforts and change things for the better.”

Note: Ciléin took part in the Science Media Centre’s Drawing Science workshop for scientists and illustrators.

No conflict of interest.

Dr Pauline Herbst, Research Fellow, LENScience Group, Liggins Institute, University of Auckland, comments:

“This paper is a wonderful addition to the canon on why it is so important that research results are available and accessible not only to the participants that take part in studies, but also to a wider audience. Academics that work across social sciences and healthcare have been writing about the process of what is called knowledge translation for decades, particularly in the various multi sensory ways comics reach audiences.

“While the authors acknowledge it was a new form for them, I was surprised not to see reference to the multiple papers by academics that have already used the forms to disseminate research; and have been pushing the discussion forward for decades.

“There is traditionally a stigma to comics being used in research outside of the humanities and this paper is a clearly thought out and presented argument for the validity of illustrated research results. It also highlights how important it is for researchers themselves to embark on a process of knowledge translation to see their own invisible bias. I welcome this paper for broadening the discussion about comics as a valid form of knowledge production in representing existing inequities in healthcare.”

No conflict of interest declared.

Professor Nancy Longnecker, Professor of Science Communication, University of Otago, comments:

“It is so refreshing to see this creative approach to sharing research results. Often, research results gather dust instead of helping to make the world a better place. Good communication can bridge that gap between researchers and those who can benefit from the findings. This study beautifully and literally illustrates creativity and an ability to walk a different path.

“The academic researchers note that they are custodians of data that their research participants have generously shared. By including a talented illustrator on their team, they have co-created valuable communication resources. The team’s reflections should inspire others to consider unconventional and potentially fruitful approaches. This has the potential to improve effectiveness of research and increase its impact.

“This work also illustrates the critical nature of flexible support from funding bodies to prioritise impactful research, foster innovation, and allow researchers to pivot and respond to opportunities.”

No conflict of interest declared.

Matt Walters, Science Communicator, University of Canterbury, comments:

“Graphical devices, such as comics, are a great way to communicate complex ideas. It is nice to see researchers reaching wider audiences with this visual format.

“These visual techniques are not new, many cultures around the world have used visual communication methods for thousands of years. Knowledge is shared in many ways, from navigation maps to carved panels and animal drawings.

“In recent years the popularity of graphic communication of complex science information has been on the rise. These include infographics and visual abstracts in scientific journals, which can be very effective if created well.

“The picture superiority effect is a design principle that means that images are remembered better than words. Graphics reduce the performance load, or effort involved in accessing information by an audience. This means they are more likely to continue than if they had to struggle through complex text.

“Storytelling through visual narratives, with the use of images, emotions and events, engage audiences deeper into the content. It also allows them to relate the content to their lived experiences. The more immersive the content is the greater focus the audience will have on it. This engagement leads to an increased depth of processing, which is a phenomenon whereby the more information is analysed the better is is remembered. This means adding images to text is better than reading the text alone.

“Comic strips are very effective as they use the technique of chunking. This is where information is divided into manageable pieces, much like eating an apple one bite at a time is easier than trying to put the whole fruit in your mouth at once. Each panel of a comic story is one chunk that can be digested before moving to the next.

“Layering the text and image content allows the viewer to scan the visuals to gain an overview of the story with very little effort. The images alone can tell a complex story, which can then be further enhanced if the viewer reads the text.

“Creative outputs, such as this, where the participants, researchers and communicators work together to tell complex stories are time consuming to create. But, the reward is that the research findings can have far greater impact than if published in a scientific journal alone.”

No conflict of interest.

Associate Professor Maurice M W Cheng, Associate Professor in Science Education, School of Education, Waikato University, comments:

“The ways that these researchers disseminated their findings were very creative! Abstract concepts such as justice, inequalities and care are notoriously difficult to be conveyed accurately through visual media. But the uptake by various public sectors showed that the research team was very successful.

“Comics by themselves do not guarantee uptake. There are several design elements in the comics that made them great communication tools. The key was that both the language and the graphics were tuned to the general public. While telling instances of everyday inequalities, the comics suggested to their audience what to do and what not to do in their everyday lives to tackle inequalities. The action-oriented communication (compared with information delivery) was exceptionally powerful in this context. The first person narrative (compared with descriptive writing) style of language was effective in communicating ideas and triggering emotions.

“I particularly like that the texts in the comic strips were printed in a sentence case. This style makes reading much easier and faster than ‘all caps’ in some other comic strips. Also, the visual elements combined very well with the verbal messages. For example, in the second strip of accessibility, the four thinking bubbles made it very concrete and specific why travelling could take much mental energy. This was just one of the many great examples in the comics of how visual and verbal elements ‘multiply their meanings’.”

No conflict of interest declared.

Dr Wiebke Finkler, Lecturer, Department of Marketing, University of Otago, comments:

“The authors, using a Toby Morris comic, highlight the importance of social listening and collaboration as central elements of visual science communication. Whether comics or other forms of visual storytelling, such as video, rapid technological and media developments offer exciting opportunities for science communication. However, how to leverage this brave new visual world of screens with skill and creativity is an important challenge that science communicators need to solve. The screen can potentially become a marketplace for science communication, but like any marketplace it is only as good as the content that flows through it: science products, ideas, information, developments and discoveries, and how they are packaged for science audiences.

“Here, science communication can learn from marketing techniques and the development of a visual rhetoric, based on social science foundational research, visual craft skills, applied media aesthetic, value-exchange and co-creation, as well as rigorous evaluation and refinement processes focused on end-users. Indeed, I’d like to argue that science communication has to do more than merely “enabling participation”, and, instead, become a driver and marketer for positive social change and impact.”

No conflict of interest.