A bioethicist’s call for young men to freeze their sperm for future use has received a chilly reception from independent experts.

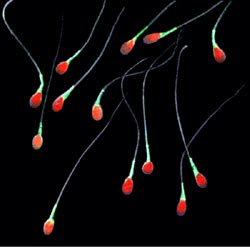

Writing in the Journal of Medical Ethics , Dr Kevin Smith, from Abertay University in Dundee, suggested state-sponsored sperm-banking as way of avoiding the complications of older fatherhood. Younger men could freeze their healthier sperm now for use later in life should they wish to become fathers.

, Dr Kevin Smith, from Abertay University in Dundee, suggested state-sponsored sperm-banking as way of avoiding the complications of older fatherhood. Younger men could freeze their healthier sperm now for use later in life should they wish to become fathers.

In making his case, Dr Smith notes that the sperm of older men contain a greater number of mutations than the sperm of younger men. Although most of these mutations are neutral or of minimal impact, “a minority of them present a risk to the health of future children,” he writes.

“If demographic trends towards later fatherhood continue, this will likely lead to a more children suffering from genetic disorders.”

Speaking to the BBC Dr Smith said “It’s time we took seriously the issue of paternal age and its effect on the next generation of children.”

Our colleagues at the UK Science Media Centre collected the following expert commentary.

Prof Allan Pacey, Professor of Andrology, University of Sheffield, said:

“This is one of the most ridiculous suggestions I have heard in a long time!

“Whilst I am aware of the evidence that has linked the risk of some genetic disorders to the age of the father, my understanding is the risks are really quite small and only become detectible at the population level once fathers get above about the age of 45 years old. It’s for this reason that the UK Professional Bodies have advised that sperm donors should ideally be below the age of 40, although some have argued that this decision is too cautious.

“Having said that, the idea that mass sperm banking for 18 years olds should be funded by the NHS is simply crackers in my opinion. For a start, we know that the sperm from the majority of men won’t freeze very well, which is one of the reasons why sperm donors are in short supply. Therefore, many men who froze their sperm at 18, and returned to use it later in life, would essentially be asking their wives to undergo one or more IVF procedures in order to start a family. In my mind, this would be a step too far in order to guard against a theoretical risk associated with older fatherhood.

“Finally, we already have trouble in some areas in getting adequate NHS funding for many cancer patients who need to bank sperm before chemotherapy and we know the provision of NHS funded IVF treatment across the country for infertile couples is way below what is recommended by the NICE 2013 guidelines. So I would say if there is any spare money around, we should be focussing it on those with a genuine infertility need, rather for some mass sperm-collection initiative where we know the vast majority of men won’t need it or use it.”

Dr Gillian Lockwood, Medical Director, Midlands Fertility Services, said:

“Although it is the case that some rare genetic conditions do increase in incidence with advanced paternal age, the financial and emotional costs of screening, freezing and storing sperm and then needing to use contraception to avoid an inadvertent conception would be far too high. IUI (intra-uterine) insemination with cryopreserved sperm is statistically ineffective (especially in older women). From work with young altruistic sperm donors, we know that not all sperm is suitable for freezing or survives the thaw and that for many couples, using this poor quality frozen sperm would require IVF or even ICSI.

“The NHS cannot currently fund even the low provision of IVF that NICE recommends, so it would be absurd to suggest that it would ever have the resources to offer ICSI to older couples who had been rendered ‘infertile’ by being precluded from using their own (fresh but ‘too old’) when a natural conception might have been possible.

“One current problem contributing to infertility is women delaying pregnancy because of social, educational, career and relationship issues, and I would worry that encouraging men to freeze their sperm might have the effect of encouraging them to delay fatherhood even more.”

Prof Richard Sharpe, Group Leader of Male Reproductive Health Research Team, University of Edinburgh, said:

“Sperm from older men undoubtedly harbour an increased number of gene mutations than sperm from young men and this may increase the risk of certain disorders in the resulting offspring of old fathers. In theory, some of these mutations might even be beneficial, although this has not been studied. The issue is so what?

“Idealistically, reproduction is undoubtedly better done young; fertility is better for women and their eggs are in better genetic condition as with the sperm in young men. But societal changes are pushing couples increasingly in the opposite direction so that sperm from an older man meeting an egg from an older woman is now much more the norm than in the recent past. Though this may not be ideal news for the health of resulting children, it should be kept very firmly in mind that the actual chances of sperm from an older man fertilising an egg from an older woman is very much reduced compared with sperm and eggs from a young couple; in part, this might be nature weeding out the defective embryos that will occur more commonly from the union of a sperm from an older man with an egg from an older woman.

“In theory, the issues resulting from sperm/eggs from an older couple can be solved by freezing sperm and eggs from couples when they are young. Easily done for the man, but requiring surgical and medical intervention in the woman. Moreover, this presupposes that the eventual bringing together of these frozen gametes during in vitro fertilisation (IVF) will guarantee a baby, but it will not, as IVF still fails in the majority of attempts.

“Last, but not least, consider costs. To keep sperm (and eggs) frozen in liquid nitrogen under fail-safe conditions for a decade or more is extremely costly as is the egg collection at the beginning and the IVF at the end. Should the NHS pay for this, when it struggles to effectively treat all the genuinely ill? This is unlikely, so the costs will be borne by the men and women. From the perspective of the older male, the gamete freezing whilst young would be to reduce the risk of passing on a harmful acquired gene mutation to his child, but as the chances of this happening are extremely low, the vast majority of men would have paid for no benefit for them or their presumptive child. Thus, the benefit to risk ratio is far too low to consider such a course of action.”

Prof Sheena Lewis, Professor of Reproductive Medicine, Queen’s University Belfast, said:

“I’m delighted that this story has highlighted the risk, although small, of delayed fatherhood. We need to tell men of these risks so they can make informed decisions and build having families into their plans as they do their careers. There have been several large studies recently suggesting that fathers over 45 have greater risks of fathering children with mental health problems and lower academic achievement. We are aware of these risks, for example in the UK we don’t accept sperm donations from men over 40 years old. However, I think sperm banking for all at 18 is unnecessary and unlikely to be a service young men would use. The time honoured way of fathering will always be preferred.”

Mr Stephen Harbottle, Chair of the Association of Clinical Embryologists (ACE), said:

“The suggestion that all men store sperm at 18 is not based upon any compelling scientific evidence and would only result in a further unnecessary financial burden on the NHS.

“Most men will father a child naturally and never return to claim their stored sperm. This would result in cryostorage facilities looking after vast quantities of unclaimed sperm akin to a left luggage store at the expense of the NHS.

“Our message is clear. People should consider starting a family earlier in life where possible, in their 20s and early 30s, to minimise age-related risks. This consideration should also be made in conjunction with other factors such as career and relationship stability.

Prof Adam Balen, Chair of the British Fertility Society, said:

(Commenting on Dr Kevin Smith’s suggestion that sperm-banking on the NHS should “become the norm” because sperm becomes more prone to errors with age, increasing the risk of autism, schizophrenia and other disorders. Dr Kevin Smith also says that artificial insemination should become the normal way for procreation and that we should have a “whole scale move away from natural conception”):

“Such a move would provide a very artificial approach to having babies. Procreation shouldn’t be taken out of the bedroom and into the test-tube unless there are defined fertility problems. There should be a greater focus in the UK on supporting young couples to establish their careers and relationships and be supported in having children at a young age before the natural decline in both female and male fertility. There is a need for better education of youngsters so that they are informed about the implications of delaying starting a family and at the same time improved societal support for working mothers and fathers with better childcare facilities to enable couples to establish careers and families.”

Declared interests

Prof Sheena Lewis is CEO of Lewis Fertility Testing Ltd, a university spin-out company marketing a test for male infertility: www.spermcomet.com

Prof Adam Balen is also Professor of Reproductive Medicine and Surgery, Leeds Centre for Reproductive Medicine.

Prof Allan Pacey: Chairman of the advisory committee of the UK National External Quality Assurance Schemes in Andrology and Editor in Chief of Human Fertility (both unpaid). Also, recent work for the World Health Organisation, Merck Sharp and Dohme Ltd (Finland), Ferring Pharmaceuticals Ltd (paid consultancy with all monies going to University of Sheffield). Co-applicant on a research grant from the Medical Research Council (ref: MR/M010473/1)