Associate Professor Euan G. Mason, from School of Forestry, University of Canterbury, and Member of the New Zealand Royal Society, has provided the SMC with a follow-up on his previous comments.

Associate Professor Euan G. Mason, from School of Forestry, University of Canterbury, and Member of the New Zealand Royal Society, has provided the SMC with a follow-up on his previous comments.

His previous commentaries, which can be found here and here, related to the impacts of the revised Emissions Trading Scheme on demand for carbon credits from new forest planting. In the article below, he provides an important clarification.

Introduction

A clarification of the government’s intentions in amending the Emissions Trading Scheme suggests that the amended scheme would create a demand for new forest planting.

New Zealand is very dependent on new forest planting to help balance its greenhouse gas (GHG) accounts, and so impacts of our emissions trading scheme (ETS) on demand for carbon credits, known in the New Zealand ETS as New Zealand carbon units (NZUs), are important.

In a release through the Science Media Centre (Mason & Evison July 2009) we outlined how the forestry sector can help mitigate climate change by sequestering carbon dioxide and also by providing more climate-friendly products and energy. A second release (Mason September 2009) compared impacts of the existing ETS with a proposed revised ETS on demand for NZUs from the forestry sector. This second release was based on a particular interpretation of a release by the Minister, Hon. Nick Smith. Most critically, it appeared to some, but not all, readers of this latter release that the intention was to provide a free allocation of NZUs to the energy sector equivalent (in proportion of GHG emissions) to that provided to agriculture (for details of this interpretation, see Appendix 1). I am grateful to Peter Weir, of Ernslaw One Ltd., for alerting me to the possibility that the energy sector might be liable for 50% of its total GHG emissions between 2010 and 2012, and for 100% of its total emissions from 2013 onwards.

Requests for clarification sent to the Minister and his staff revealed that demand would very likely be significantly greater than that initially estimated. Most significantly, to the question, “Just so we are crystal clear on this, could you please confirm that ‘All Energy’ will be liable for 32,653,000 NZUs in 2013 if their emissions stay at 2007 levels?”, George Riddell, a Senior Advisor on Climate Change Issues for the Minister responded:

“First let us be clear that 1 NZU must be surrendered for every tonne of greenhouse gas emissions therefore using the figures you have used 75,550,000 NZU’s will need to be surrendered each year. However the Government will, to protect the export sectors, allocate some 43,000,000 units free of charge. The difference is some 32,000,000 p.a. which will need to come from the forestry sector or from off-shore. So around the figure you came up with and as you say should encourage planting at a reasonably high level starting now.”

Assumptions

Before examining the implications of this response on likely demand for NZUs it is important to clarify the impacts of some critical assumptions upon which projections are based. Some of the key ones affecting demand until 2020 for NZUs are:

- The extent to which owners of existing post-1989 (“Kyoto”) forests register for the scheme. Kyoto forest owners can choose whether or not to register for the ETS. Registration means that they can claim and sell NZUs, but then they are also liable for NZUs when they harvest. A prominent Kyoto Forest owner wrote to me suggesting that, owing to perceived low returns in the proposed scheme and future liabilities, as little as 15% to 20% of Kyoto forest owners might register. I think these are low estimates, but if he is right then of course this would increase future NZU demand. It would also mean that forest owners had granted a gift to the nation of free sequestration that allowed us to pollute more without incurring extra costs.

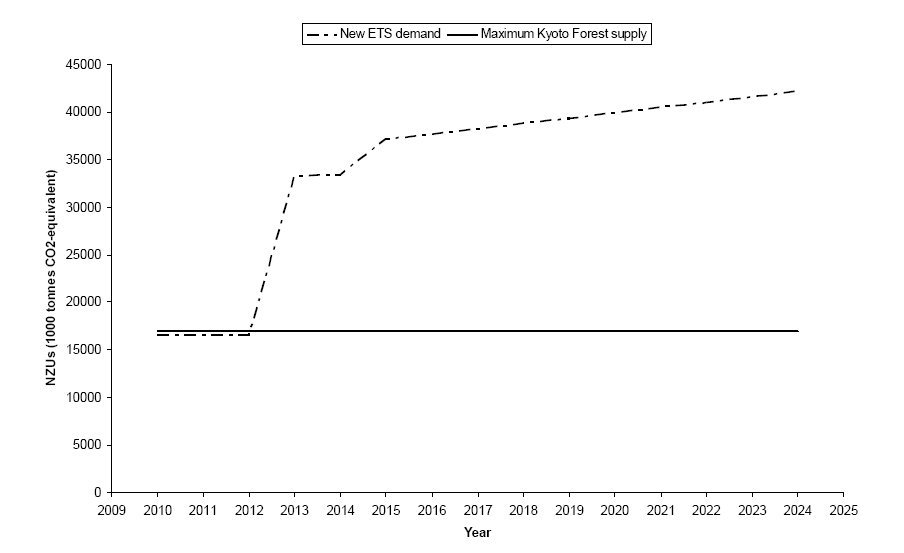

- The precision of estimates of forest C sequestration. Figure 2 shows a theoretical maximum supply from existing post-1989 forest, but if inventories of carbon sequestration were poor then this would reduce NZU supply from those forests, in accordance with ETS rules. Poor inventories in new forests would also increase the area of such forest required to meet demand.

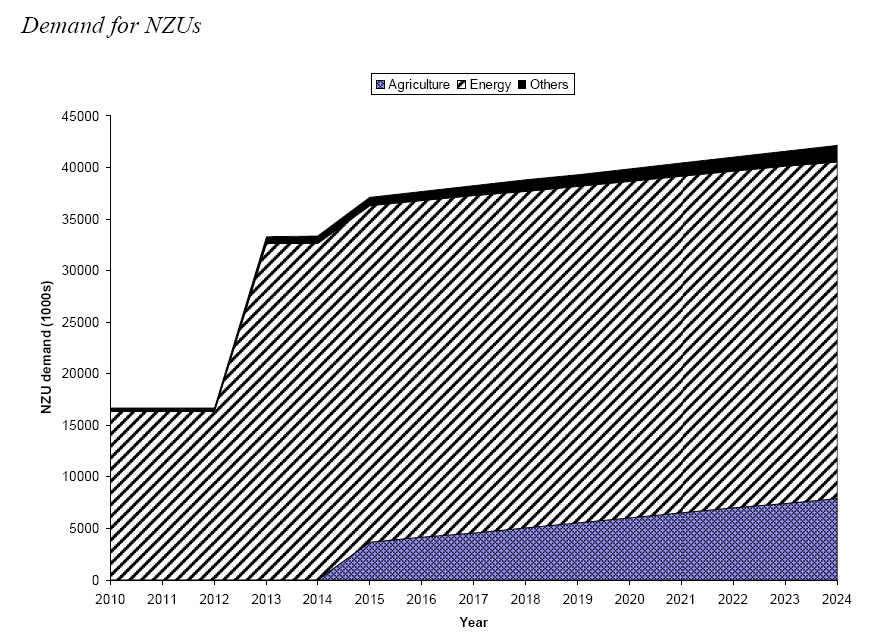

- The speed of changes in behaviours in other sectors. If other sectors reduced emissions, either by employing new technologies or through decreased production, then demand for NZUs would be reduced. The key sector here is the energy sector, that is liquid fossil fuels and stationary energy (including electricity), which would provide almost all the demand for credits in the short term (Figure 1). There may be a tendency for large energy companies to internalise their NZU supply by purchasing forests or entering into joint ventures with land owners.

In addition, the projections examine only short term NZU demand, and from around 2017 onwards growers who planted during the 1990s (Kyoto Forest owners) will increasingly face decisions about whether or not to harvest their crops in any particular year. If they chose to harvest then this would substantially add to the demand for NZUs during the 2020s. If they had previously registered for the ETS, a high price for NZUs would make harvesting less likely. If they mostly chose not to register for the ETS because of perceived low returns then their free “gift” to the nation would effectively be withdrawn when they harvested and we would have much more difficulty in meeting our international commitments to reduce net GHG emissions during the 2020s. If, however, many of them register for the ETS and they decide to proceed with harvesting during the 2020s, then they will add to the demand for NZUs because at time of harvest they will have to surrender a proportion of those they had previously earned.

Returns to growers from new afforestation will also be influenced by the degree to which exports of NZUs are restricted. This is known for Kyoto Commitment Period 1 (2008-2012) but may be different for Commitment Period 2. The remaining NZUs that can be exported during period 1 without foreign purchases of NZUs is now 24 million, with a right to export 16 million allocated to pre-1990 forest owners for the loss of the right to deforest without financial penalty. With lower domestic demand for NZUs from the proposed ETS, restricted export capacity will be a concern for those contemplating investment in new forests.

Demand for NZUs

Figure 1 – Likely sources of demand for NZUs by sector, assuming emissions remain at 2007 levels.

Figure 2 – Demand for NZUs assuming emissions remain at 2007 levels compared to a theoretical maximum supply for existing Kyoto forest.

Sources of demand by sector are shown in Figure 1. The energy sector will initially have the biggest shortfall between free credits and GHG emissions. Demand shown in Figure 1 was calculated by assuming that emissions remained at 2007 levels.

The difference between demand and theoretical maximum supply from existing Kyoto forests is shown in Figure 2. Kyoto forests are unlikely to provide this maximum supply because not all owners of these forests will register, and estimates of CO2 sequestration from their forest inventories will be imprecise, thereby reducing the NZUs they can claim under ETS rules.

Area of new forest required to meet demand

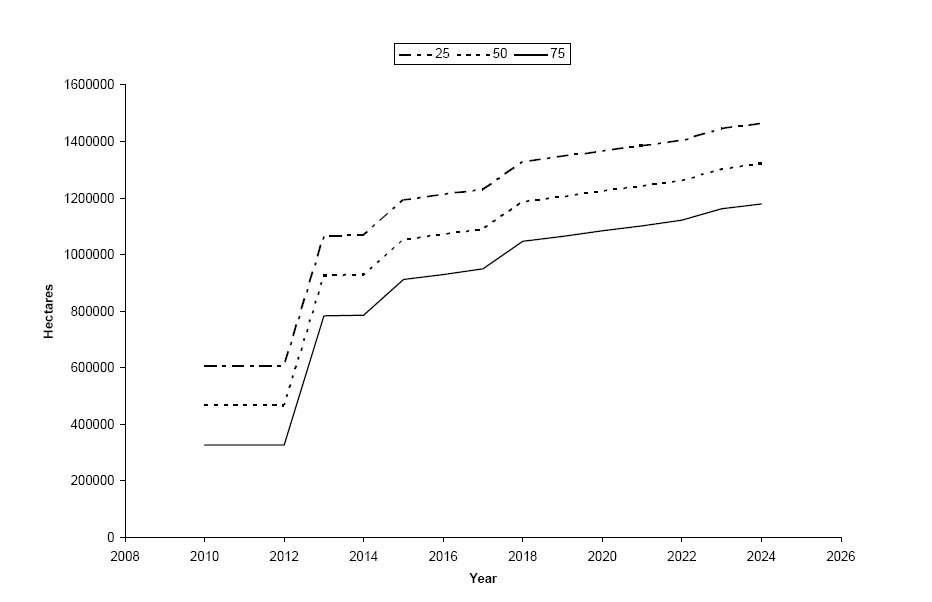

It is feasible to estimate the number of hectares of new plantation required to satisfy domestic demand assuming that:

- Emissions remain at 2007 levels;

- Exports of forestry-related NZUs during commitment period 1 are 24 million, the maximum allowed;

- 16 million NZUs are allocated to pre-1990 forest owners during commitment period 1 (from 2008-2012), and 50% of these are used for deforestation while a further 10% are carried forward to commitment period 2 (yet to be determined, but assume 2013-2017).

- 34 million NZUs are allocated to pre-1990 forest owners during commitment period 2, and they are used in equivalent proportions to those allocated during commitment period 1.

- 30 million forestry-related NZUs are exported during commitment period 2;

- There are no imports of carbon credits;

- Owners of existing Kyoto forest provide NZUs to the market at rates of either 25%, 50% or 75% of the theoretical maximum supply; and

- New forests can sequester CO2 at a rate of 30 tonnes/ha/annum. If most new forest is planted on marginal land then sequestration could be less than this. Note also that forest takes a few years to reach this level of sequestration.

Adopting these assumptions yields cumulative areas of new forest required to fully meet demand as shown in Figure 3.

Forest owners cannot immediately meet any given demand for NZUs, because establishing forests requires careful planning and investment. There are also constraints on planting rates in the short term due to nursery capacities and also numbers of contractors, and so meeting a demand for almost a million new hectares by 2015 (Figure 3) would stretch resources in the sector. The most new forest planted in New Zealand during any one year was 98,000 ha in 1995.

In addition generous free allocations of NZUs to the agricultural sector will probably keep land prices high, and that will likely reduce levels of investment in new planting.

Figure 3 – Cumulative areas of new forest required to meet demand, with assumptions outlined above, assuming that planting is required for demand above 25%, 50% and 75% of the maximum potential supply from existing Kyoto forests.

Impacts of changes in behaviour in other sectors

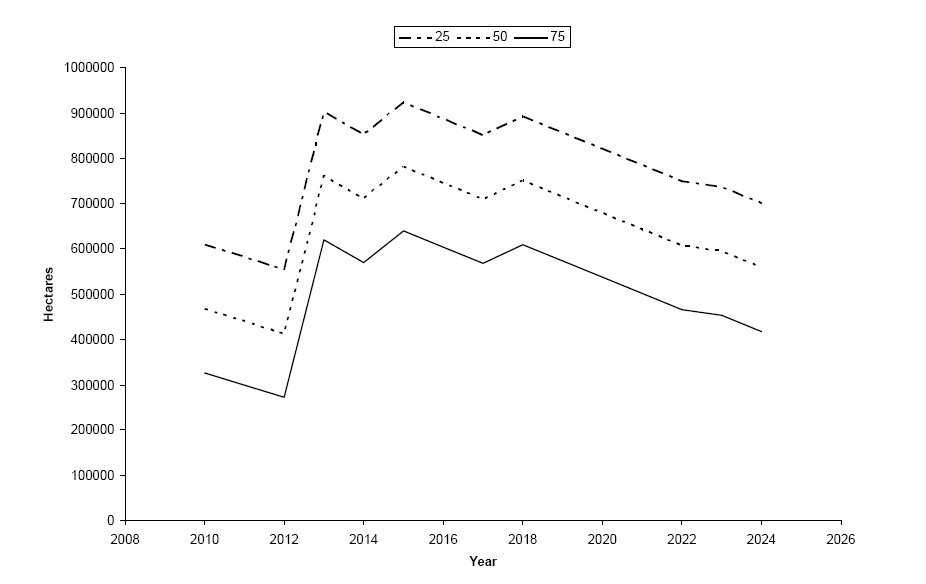

If other sectors adopted new technologies or reduced output in response to the ETS, then demand for forest-based NZUs would be markedly curtailed. The extent to which this might happen is difficult to estimate, but the impact is clear. Assume, for example, that the energy sector reduced its GHG emissions by 5% per year (using 2007 as a base year) from 2010 and the resultant areas of new forest required to fully meet demand for NZUs are shown in Figure 4.

Grey carbon credits

In September 2007 Meridian Energy offered carbon credits for sale on TradeMe that had reportedly been accrued by building a wind farm instead of building a power plant that would have emitted GHGs. If free NZUs were allocated under these circumstances, then this would impact on demand for forest-based NZUs.

NZUs allocated for “avoiding GHG emissions” are markedly different from those earned through GHG sequestration. For convenience, let’s call the former “grey NZUs” and the latter “green NZUs”. With a rationally administered ETS the reward for avoiding emissions should be that one is not required to purchase and surrender green NZUs. Grey NZUs, if allowed, would debase the currency of NZUs and could undermine the ETS. Consider, for example, a forest owner that claimed, “I was going to harvest and emit GHGs, but I decided not to and I should therefore be allocated NZUs in addition to any I might earn through sequestration in future”. This is patently absurd, but it is equivalent to a power company claiming NZUs for a decision not to emit GHGs.

Figure 4 – Area of new forest required to fully meet domestic demand for NZUs assuming a decline in energy sector GHG emissions of 5% per year, and existing Kyoto forest supply of 25%, 50% and 75% of potential maximum.

Final comment

Proposed amendments to the New Zealand Emissions Trading scheme will bring to an end a period of uncertainty generated by a review of the existing scheme, and this reduced uncertainty will be welcomed by potential investors in new forests. It is likely that the ETS will result in both new planting and reductions in gross GHG emissions.

Acknowledgements

I am grateful for helpful information and feedback on my earlier release from David Evison, Peter Weir, Ian Telfer, Peter Clark, Derrick Parry, and Roger Dickie.

Appendix 1 – The alternative interpretation of proposed changes to the ETS

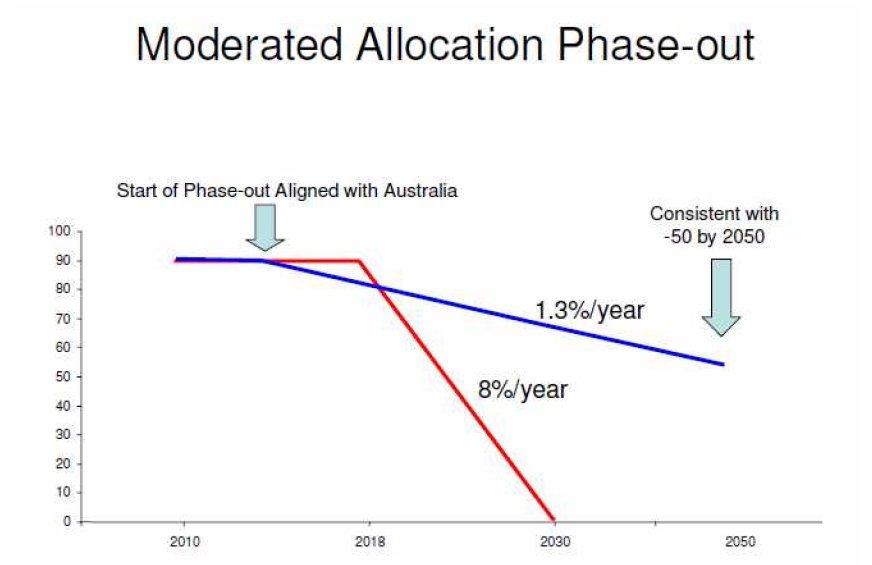

The Minister’s initial release (14th September 2009) contained a graph as (Figure A1) that suggested an allocation phase out that was consistent with a 50% reduction in total GHG emission by 2050.

Figure A1 – Graph of free NZU allocation phase out from the Minister’s release The only way that my simulation could yield a projected demand for NZUs that was close to 50% of emissions in 2050 was by assuming that large allocations of free credits were granted to the energy sector, and that the statement in the Minister’s release of “a transitional phase until 1 January 2013 with a 50% obligation and $25 fixed price option for the transport, energy and industrial sectors” applied to obligations above this free allocation. After the clarification supplied by Mr Riddell I calculate a domestic credit demand of approximately 75% of total emissions in 2050, and therefore the Minister’s statement must have been meant to refer to a reduction in gross emissions (which makes the graph reference difficult to understand).