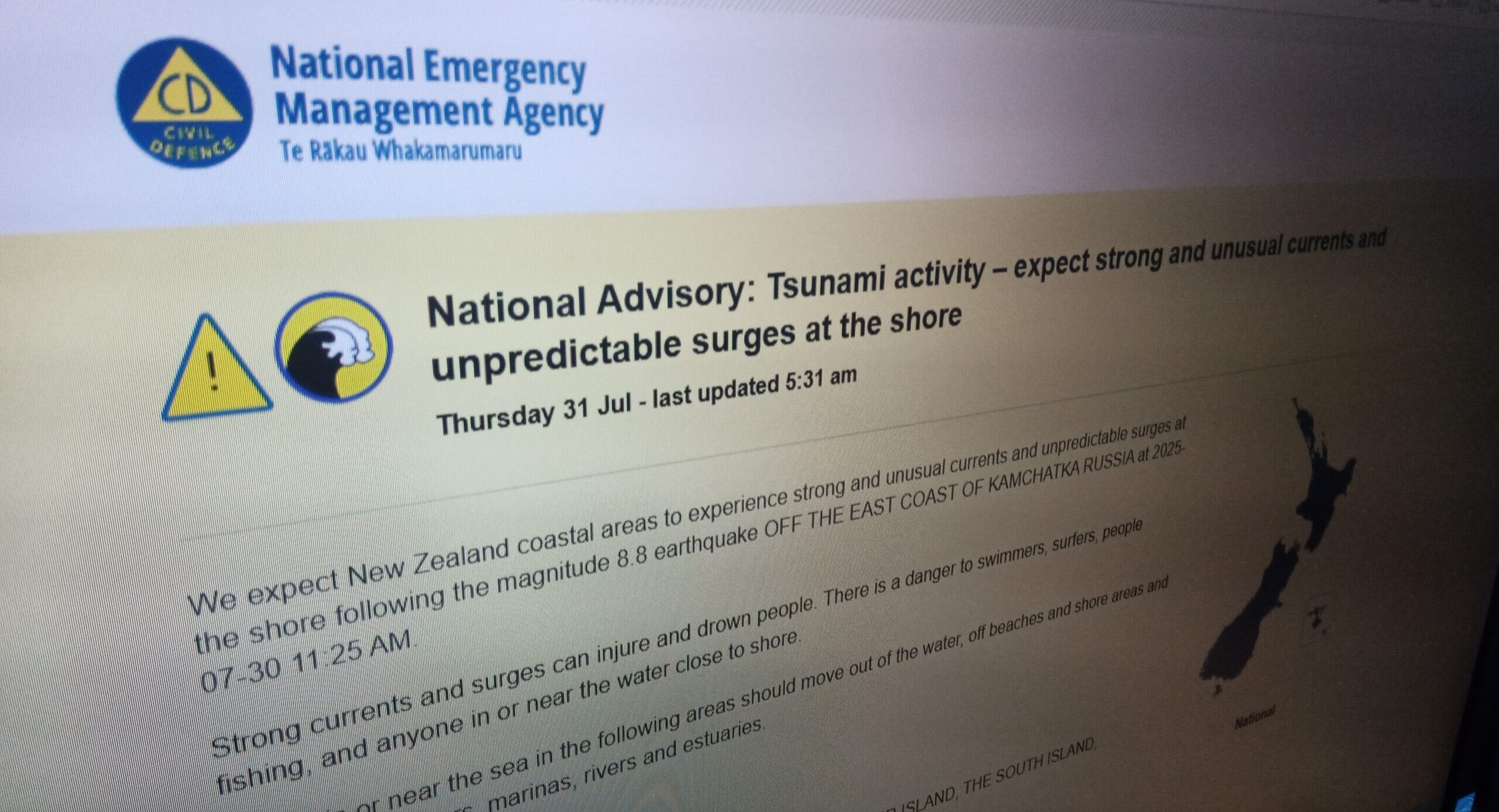

Many New Zealanders awoke at 6:30 am to a tsunami alert blaring from their phones, after yesterday’s magnitude 8.8 earthquake near Russia – one of the strongest ever recorded.

The alert warns people to stay away from the coasts, which may experience “strong and unusual currents and unpredictable surges” until at least midday today.

A glitch also resulted in some people receiving the alert multiple times, or not at all.

The SMC asked experts to comment on the decisions that go into sending emergency alerts.

Yesterday’s expert comments on the earthquake are available on our website. Our colleagues at the UK SMC have also gathered comments.

Dr Sally Potter, social scientist and warnings consultant, Director of Canary Innovation Ltd., comments:

“Many people around New Zealand received two Emergency Mobile Alerts over the past 24 hours. While these can be disruptive if you’re tucked up safely at home, they may well have saved lives too. Perhaps they made people rethink going out early this morning to fish or surf, or for a walk on the beach. It’s important for emergency managers to ensure they are doing everything they can to inform people about life-threatening risks such as tsunami.

“Following the 2022 eruption of the Hunga volcano in Tonga, tsunami surges reached our shores. Similar to today’s event, there was a beach and marine threat, and the surges caused damage to boats in harbours, particularly in Northland. A campsite was also flooded in Canterbury. So, we need to make sure we take all alerts such as this seriously, particularly due to the uncertainties involved in the locations affected, timing and how big the event is going to be.”

No conflicts of interest.

Dr Lauren Vinnell, Senior Lecturer of Emergency Management, Joint Centre for Disaster Research, Massey University, comments:

“The Emergency Mobile Alert system is a valuable resource for communicating information about imminent hazards to the public. It’s a tough balance between not alerting too much that people become tired of them and pay less attention in future, but not alerting too little so that people feel they haven’t been adequately warned. Tsunami do pose a real risk to life, so the use of the system today and yesterday seems appropriate. One way to avoid complacency when people do receive alerts but don’t experience danger personally is to encourage them to view these alerts as practice, so that they will be better prepared to respond next time.

“It is also vital to remember that while we have this alerting system, it won’t always be possible to get warnings to people in time. It’s important that efforts to teach natural warning signs, like a long or strong earthquake for tsunami, continue. This will mean that people are better equipped to respond to alerts if they do get them, but also will be more prepared to act to keep themselves safe in the instances where official warnings are not possible.”

No conflicts of interest.

Professor Tom Wilson, National Emergency Management Authority (NEMA) Chief Science Advisor, comments:

What options are available for emergency communication in this sort of context?

“The National Emergency Management Agency, and the wider Civil Defence Emergency Management sector, uses a “multi-channel” approach to informing people of tsunami threats. What this means is we try use multiple communication pathways or channels to reach everyone who needs to know. This includes media, information on websites, and social media.

“No one channel is ‘failsafe’ or effective at reaching everyone. So, we issue information on as many channels as possible to ensure there are a variety of ways people can stay informed, even if some channels fail. This includes Emergency Mobile Alerts when there is a serious threat to life.

“For a local-source tsunami, which can arrive in minutes, there is not enough time for an official warning. It is important people recognise the natural warning signs and act quickly. Remember, Long or Strong, Get Gone.

“A key part of this is the expectation that people will share this warning with their family/whanau, friends, workmates, etc. so the warning is spread rapidly. Also, when people receive warnings from multiple trusted sources, especially including trusted family and friends for example, it helps people trust the warning and take action.

“Effective warnings start a long way before a ‘event’ happens. An effective early warning system is made up of four elements:

- disaster risk knowledge,

- detection, monitoring, analysis, and forecasting,

- warning dissemination and communication, and

- preparedness and response capabilities.

“A key part of any effective warning system is everyone who may need to act on a warning, understands why they may need that warning. Public education is important for this to help individuals and communities understand the risk(s) they are exposed to, what warning they may receive, what the warning means, and what actions to take. But we try ensure the warnings we send out have all the necessary information needed for people to make good decisions.

“NEMA has translated information about what to do before, during and after a tsunami in a number of languages and alternate formats – to ensure as many people can understand and act on the natural warning signs and official warnings. This is available at getready.govt.nz.

“This overall warning system approach has been informed by and developed with evidence from NZ and international social science on warnings and risk communication, such as from Massey and Earth Science NZ social scientists.”

What’s the process for decision-making on alerts and emergency communication?

“It is a structured process; where an alert will come into NEMA’s Monitoring Alerting and Reporting Centre, which is a 24/7 capability, who then follow a standard pre-determined procedure – depending on the nature of the event. In the case of tsunami, the Centre receives alerts from the National Geohazard Monitoring Centre, which is run by Earth Sciences NZ (formerly GNS Science); and the Pacific Tsunami Warnings Centre.

“If a tsunami which could affect NZ is possible, the National Controller and other key NEMA operational staff convene to determine if a warning should be issued. The response indicators used by NEMA, and the type of Warning or Advisory message that may be issued are set out in the National Tsunami Advisory and Warning Plan. If a very rapid warning is required (e.g. something with impending life-safety risk such as a large earthquake just off the coast of NZ) this will be a very rapid process. NEMA has predefined National Warning templates for these situations. This is underpinned by a huge amount of scientific modelling and analysis, which helps identify the various sources of a tsunami and which communities may need to evacuate.

“NEMA’s decision-making is informed by the ‘Tsunami Experts Panel’ which is an essential service GeoNet, part of Earth Sciences NZ, provides to NEMA and the wider Emergency Management sector. The Panel is a group of tsunami experts who provide a forecast of the likely extent, wave weight at NZ coastline, and arrival time of tsunami. They will swing into action as rapidly as possible (usually within minutes of a large event) to deliver science advice as rapidly as possible.

“If there is a bit more time (e.g. a distance source tsunami, like the tsunami yesterday which took greater than 12 hours to get to NZ) then a wider team at NEMA will consider what additional public messaging may be required. This will be done in coordination with other partner agencies depending on the event e.g. regional CDEM Groups, Police, etc.”

What else should we be aware of?

“This is a great time to increase your knowledge on tsunami risks. We encourage people to familiarise themselves with the tsunami evacuation zones for their area and know where to go. People can search their home or work address on the nationwide tsunami evacuation zone map.

Conflicts of interest: None declared.

Dr Ulrich Speidel, Senior Lecturer, School of Computer Science, University of Auckland, comments:

“New Zealand has struggled in the past to get tsunami warnings out in time. This time, we had plenty of warning given that the quake was so far away. The phone alert system also worked well, except that many people apparently received multiple emergency alerts from Civil Defence. I got eight in total. Now that’s obviously something that needs looking at, although I guess most of us would rather get eight warnings than none at all.

“Japan and Hawaii in particular have taken past tsunami as design input to their early warning systems, and tend to be much better prepared than NZ. Coastal evacuation in Japan tends to be well rehearsed nowadays. One of my collaborators is the research lab of a large Japanese Internet Service Provider. They can literally have Tokyo disappear off the map without losing the rest of their network.

“I have also personally been able to observe the Hawaiian approach during a tsunami warning there in 2012. They take this incredibly seriously: Almost all of Waikiki was evacuated, literally tens of thousands of tourists, and it’s impossible to miss what is happening.”

Conflicts of interest: None declared.