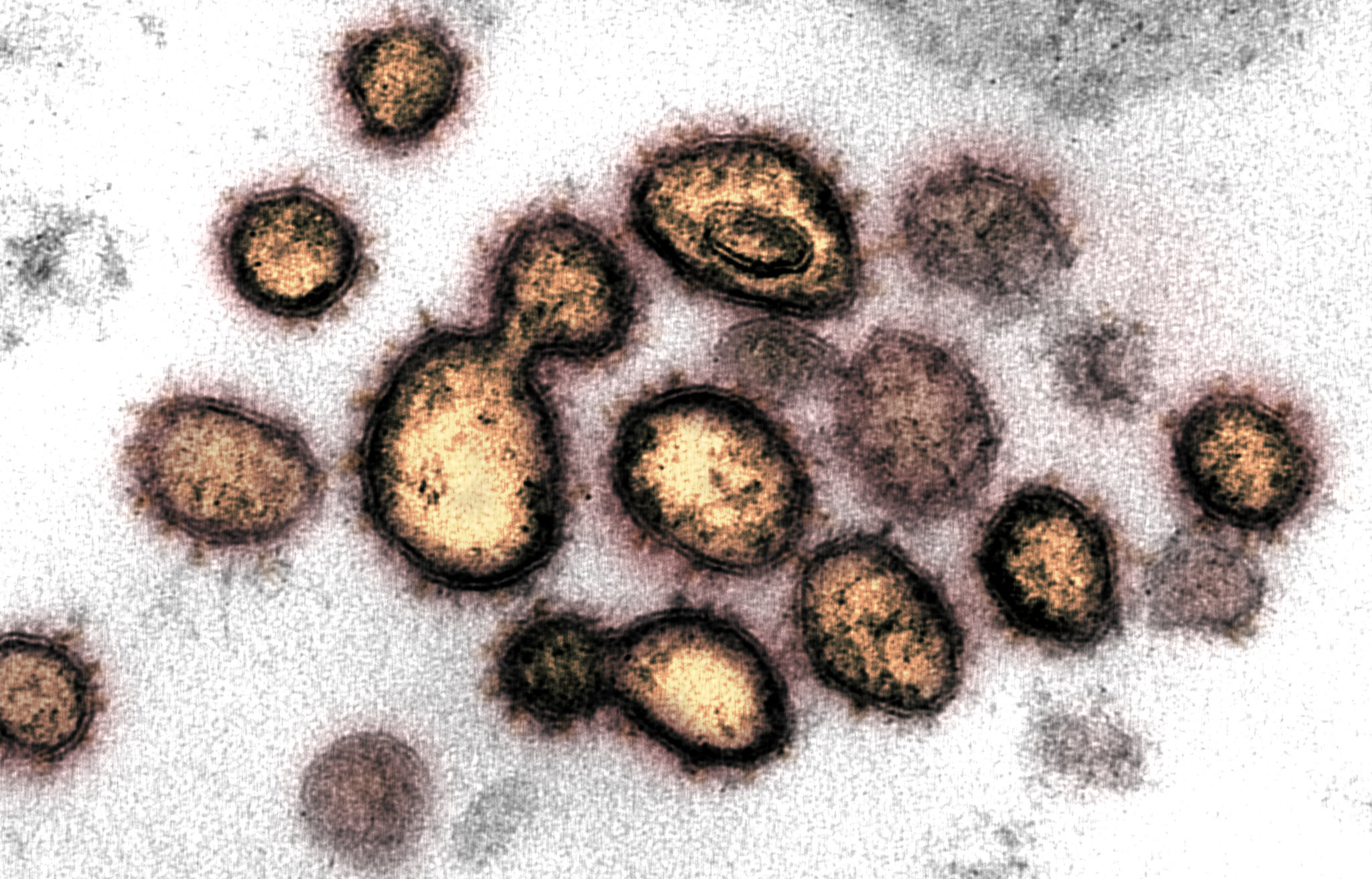

There are reports that a new variant of SARS-CoV-2, the virus that causes COVID-19, has been found circulating in parts of the UK.

UK Health Secretary Matt Hancock said at least 60 different local authorities had recorded Covid infections caused by the new variant.

The following expert comments have been collected by our colleagues at the UK Science Media Centre.

Dr Lucy van Dorp, senior research fellow in microbial genomics at the UCL Genetics Institute, comments:

“It is frustrating to have claims like this made without the associated evidence presented for scientific assessment and the variant remains to be officially announced. It seems COG-UK will release further details soon and a preprint may follow.

“The possible candidates based on some of our own observations (current as of 30th November) is that this may refer to a double deletion in the coronavirus spike protein (positions 69/70) or alternatively a spike mutation in the receptor binding domain N501Y. There is some experimental support for N501Y increasing receptor binding experimental settings and mouse models. There have also been some reports that the spike double deletion has a moderate impact on antibody recognition.

“At the same time it is important to remember that all SARS-CoV-2 in circulation are extremely genetically similar to one another and our prior should be that most mutations have no significant impact on the transmissibility of SARS-CoV-2. However genomic monitoring is essential to allow us to stay one step ahead.”

Prof Jonathan Ball, Professor of Molecular Virology, University of Nottingham, comments:

“The genetic information in many viruses can change very rapidly and sometimes these changes can benefit the virus – by allowing it to transmit more efficiently or to escape from vaccines or treatments – but many changes have no effect at all.

“Even though a new genetic variant of the virus has emerged and is spreading in many parts of the UK and across the world, this can happen purely by chance. Therefore, it is important that we study any genetic changes as they occur, to work out if they are affecting how the virus behaves, and until we have done that important work it is premature to make any claims about the potential impacts of virus mutation.”

Dr Simon Clarke, Associate Professor of Cellular Microbiology at the University of Reading, comments:

“Health Secretary Matt Hancock has linked the discovery of a mutation in the virus’ spike protein to increased transmission; while that is yet to be verified, it would be of grave concern if it indeed proves to be the case. While Hancock states that there is “nothing to suggest” this variant will cause more serious disease, if it spreads more readily than other versions, infecting more people, it could eventually take a bigger toll on human health.”

Dr Zania Stamataki, Viral Immunologist, University of Birmingham, comments:

“The emergence of different coronavirus strains a year after SARS-CoV-2 first jumped to humans is neither cause for panic nor unexpected. Mutations will accumulate and lead to new virus variants, pushed by our own immune system to change or perish.

“This virus doesn’t mutate as fast as influenza and, although we need to keep it under surveillance, it will not be a major undertaking to update the new vaccines when necessary in the future. This year has seen significant advances take place, to build the infrastructure for us to keep up with this coronavirus.”

Prof Jonathan Stoye, Group Leader, Retrovirus-Host Interactions Laboratory, The Francis Crick Institute, comments:

“Genetic variants arise relatively frequently in viruses as a result of errors in copying viral genetic material. These can lead to small changes in virus proteins.

“Such changes may improve virus replication and make SARS-CoV-2 grow a little faster. Such a genetic variant may outgrow other viruses in an individual, and is thus more likely to spread to other people. In a short time, a virus carrying such a genetic change will predominate in the population.

“There are several precedents for SARS-CoV-2 viruses arising with enhanced growth properties but no evidence that any of them cause worse disease. However, viruses with altered genomes may also increase in number simply because they arose in someone who happens to infect a lot of other people, perhaps in a crowded gathering, rather than because the virus has changed properties.

“Experiments with purified viruses to test whether observed genetic changes result in altered properties of the virus will be needed to distinguish between these possibilities. Use of such virological analyses is a vital tool for the further monitoring of potential virus evolution as the COVID-19 pandemic unfolds.”

Dr Jeremy Farrar, Director of Wellcome, comments:

“While research is ongoing, there is evidence to indicate a new variant of the Covid-19 virus. There have been many mutations in the virus since it emerged in 2019. This is to be expected, SARS-CoV-2 is an RNA virus and these viruses mutate and change. The pressure on the virus to evolve is increased by the fact that so many millions of people have now been infected. Most of the mutations will not be significant or cause for concern, but some may give the virus an evolutionary advantage which may lead to higher transmission or mean it is more harmful.

“The full significance of this is not yet clear – that includes whether a new strain is responsible for the current rise of infections in parts of the UK and, if so, what this may or may not mean for transmission and the efficacy of the first vaccines and treatments. This is potentially serious; the surveillance and research must continue and we must take the necessary steps to stay ahead of the virus.

“Above all, this is a reminder that there is still so much to learn about Covid-19. The pace of the research effort in the past year has been extraordinary, allowing us to make significant progress on the vaccines, treatments and diagnostics needed to end this crisis. The speed at which this has been picked up on is also testament to this phenomenal research effort. However, there is no room for complacency. We have to remain humble and be prepared to adapt and respond to new and continued challenges as we move into 2021. This pandemic is not over and there will still be surprises in the virus, how it evolves and the trajectory of the pandemic in the coming year.

“2020 has been a tough year; tough beyond belief for millions across the country, and across the world. Unfortunately, more difficult months lie ahead and the consequences of relaxing our focus or not having sufficient restrictions will result in more suffering. We have to respect the restrictions and accept that there will be a need for these to be tightened when infection rates rise, or as new information is learned about this virus.”

Prof Julian Hiscox, Chair in Infection and Global Health, University of Liverpool, comments:

Is this to be expected?

“Yes, this has been known for many years with coronaviruses. Coronaviruses have two mechanisms of mutation. If we look at animal coronaviruses, such as infectious bronchitis virus of poultry, there are hundreds of different variants of that virus. There are many different variants of the different seasonal human coronaviruses, and with those people can become reinfected within six months to a year.

Are new variants always more virulent?

“No, not always, but in feline (cat) coronaviruses, within host change in a single infection can lead to a new more virulent virus being formed. In other coronaviruses, some have ‘changed’ that have become less virulent e.g. pig coronaviruses.

Is this a big deal? Should we be alarmed? How should it change our response, if at all?

“We should be cautious and focus efforts on understanding the transmission of this virus and if necessary introducing control measures to prevent its spread. There is always a lag between sampling and information. Currently there is no evidence that this virus will evade the vaccine or will lead to increased disease or death.

What will PHE be doing to analyse it? What do we need to know about it?

“PHE will be focusing on sequencing the virus from patients to determine its prevalence in the population and conducting analysis of the biology of the virus e.g. does it grow more quickly or the same as other strains. They will also be checking that the nucleic acid based diagnostic remain fit for purpose as many of these target the spike gene. This illustrates why we need a rapid mechanism in the UK to understand these so called genotype to phenotype changes.

Why should we be confident that it will still respond to the vaccines?

“We know from other coronaviruses that small changes in the spike glycoprotein (that is the target of the vaccine) can lead to vaccine escape. We have no evidence at the moment whether this variant will or won’t respond to the vaccine. This illustrates that we need to be agile and flexible with the vaccine platforms and will probably be like seasonal influenza viruses where we have to give multiple vaccines that change with time.

How different do variants need to be for one to resist a vaccine?

“This depends on where the variants are located in the vaccine target. If this is in what is called the receptor binding domain of spike then variants may be refractive to the vaccine. This illustrates why for most animal coronaviruses the vaccines are multi-valiant i.e. target a number of different viral proteins.”