Ex-tropical cyclones smash into New Zealand almost annually.

Their violent winds, torrential rainfall, and associated storm surges have been felt in communities across the country.

With ex-tropical cyclone Uesi heading for the lower South Island – which is still recovering from last week’s flooding – the Science Media Centre asked MetService for answers to commonly asked questions about this type of weather event.

Chris Noble, MetService Manager Severe Weather Services, and Chair of the Tropical Cyclone Committee for the South Pacific and South-East Indian Ocean, comments:

What is a tropical cyclone?

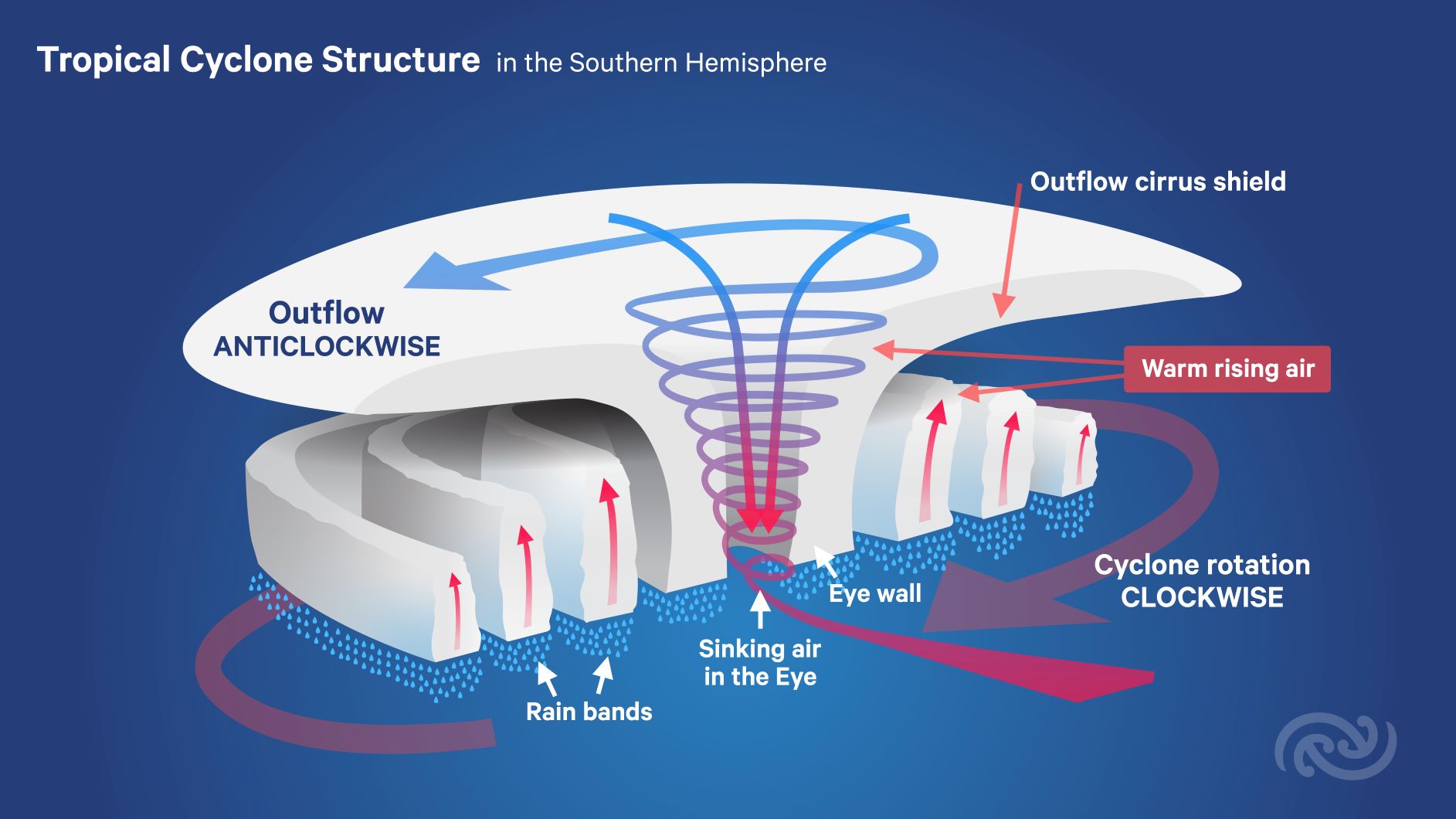

“A tropical cyclone is a low-pressure system which forms over warm waters in the Tropics and has gale force winds (63km/h or more) at low levels near the centre (winds turning clockwise in the southern hemisphere), with organised convection (i.e. thunderstorm activity).

“The gale force winds can spread out hundreds of kilometres from the centre of the cyclone, and if the winds reach 118km/h then the system is called a Severe Tropical Cyclone.”

When do we get tropical cyclones?

“The South Pacific tropical cyclone season is typically from November to April. On average, about 10 tropical cyclones form in the South Pacific tropics each year, and about one of those will affect New Zealand as an ex-tropical cyclone (most commonly in February or March).”

What are the different categories of tropical cyclones?

“Tropical cyclones are categorised by their wind speeds. This table outlines how tropical cyclones are categorised under the Australian and South Pacific category system used by the Fiji Meteorological Service and the Australian Bureau of Meteorology (any tropical cyclones that impact New Zealand originate from these regions and are normally no longer ‘tropical’ when they reach us).

Who is watching for tropical cyclones?

“Internationally there are six Regional Specialised Meteorological Centres (RSMCs), together with six Tropical Cyclone Warning Centres (TCWCs), which have regional responsibility to provide tropical cyclone warnings and related bulletins.

“MetService runs TCWC Wellington, so all official warnings and advisories about tropical cyclones that could affect New Zealand originate from MetService.”

Who names tropical cyclones?

“During the tropical season, MetService’s expert tropical meteorologists routinely monitor output from global weather modelling centres and scrutinise observational data to see if there is potential for a tropical cyclone to form. Once a system meets the criteria, it is named as a tropical cyclone by the relevant WMO, RSMC, or TCWC that has the sole authority to name a cyclone.”

How are tropical cyclones monitored?

“Once a tropical cyclone is named, and often in the lead up to naming, warnings are issued and forecast track maps are produced normally every six hours out to 72 hours (three days). Forecasting a tropical system means first making a thorough analysis of what is happening now in terms of both intensity and position. The analysis is formed using a wide variety of observational data, such as satellite images, scatterometer ocean wind data as well as land and ship-based automatic weather stations. This analysis is compared to computer model output, and forecasts are adjusted based on differences between the model and the real world.”

How is this monitoring evolving?

“The forecasting of tropical cyclones, like all of meteorology, is a global challenge with weather systems and their hazards routinely crossing international borders. Through agreements under the World Meteorological Organisation (WMO), MetService work closely with other countries to share data and improve observation networks across the Pacific which are of great value to forecasters. Numerical weather models have improved significantly in the last 20 years, particularly in the long range with advances in ensemble modelling, as have satellites which now provide a wealth of data across all ocean areas where cyclones form. These advances are only possible because of the international and collaborative nature of the World Meteorological Organization (WMO) and its members and have improved tropical cyclone forecasting worldwide.”

How challenging is it to forecast a tropical cyclones?

“Tropical cyclones are complex systems embedded within the already complex atmosphere producing our weather. Uncertainty in the initial analysis means it is important to avoid placing too much value on a single future solution or just one model run, especially when there are long lead times. The expertise of a meteorologist with a thorough understanding of atmospheric dynamics is vital in interpreting computer model output as it relates to cyclones.

“Once the cyclone track forecast is produced, the next task then is to communicate the message to the public including the risk of hazardous weather. Because tropical cyclones are among the most damaging weather systems, National Meteorological Services want to give as much warning as possible. However, early warnings need to be carefully balanced with the uncertainty in future hazards to avoid over-alerting unnecessary hype as cyclones can and sometime do change track resulting in a large change in the nature and distribution of their hazardous weather.”

Will climate change affect the tropical cyclones we get in the future?

“Advice from climate scientists via the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change suggests that while globally the number of cyclones may remain essentially unchanged, they are expected to become more severe under a warming climate, producing stronger winds and more intense rain.”