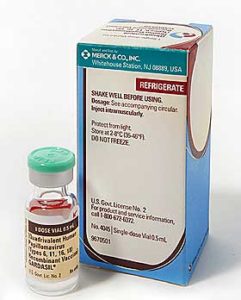

Research published today in the Journal of the American Medical Association gives some fairly compelling, if not conclusive evidence that the HPV vaccine Gardasil is safe for the young girls it is targeted at.

You might think that should be a given, but vaccines and their interaction with people is complex and trials don’t always indicate the problems that will be encountered when the vaccine is unleashed on the population at large. As the HPV vaccine programme has been controversial, both here and in the US, this is nevertheless important reassuring news. Some parents and potential recipients of the vaccine have been reluctant to receive it because they have often unwarranted concerns about its safety as this Herald story illustrates:

You might think that should be a given, but vaccines and their interaction with people is complex and trials don’t always indicate the problems that will be encountered when the vaccine is unleashed on the population at large. As the HPV vaccine programme has been controversial, both here and in the US, this is nevertheless important reassuring news. Some parents and potential recipients of the vaccine have been reluctant to receive it because they have often unwarranted concerns about its safety as this Herald story illustrates:

Asked whether she had received the HPV vaccine, year 12 student Rosie Rogers commented: “I didn’t really know much about it, then my friend came to school and said someone her mum knows got sick from it. So I researched it and apparently it hasn’t been fully approved. We’re kind of like the guinea pigs for it, and I heard it sometimes risks your chance of getting pregnant.”

Where did all of that come from? Second hand news and Google searches it seems. After all, many New Zealanders are self-diagnosing their health problems on the web these days.

With 23 million doses of the HPV vaccine delivered in the US, problems have been encountered in less than 1 per cent of vaccine recipients and only a tiny minority of cases reported through the Vaccine Adverse Events Reporting System (VAERS) were considered serious. Counted among those serious reactions are 32 deaths which sounds alarming. But the passive method of reporting of the adverse reactions doesn’t determine one way or other if the deaths are due to the HPV vaccine. The experts writing in JAMA point out further monitoring over a longer period is necessary but conclude that: “The postlicensure safety profile presented here is broadly consistent with safety data from prelicensure trials.”

It was the safety profile of those trials of 21,000 vaccine recipients that encouraged the Ministry of Health to give Gardasil the green light here.

Still, even if Gardasil is safe, is it effective in battling cervical cancer over the longterm? That’s the question posed in JAMA‘s editorial by Dr Charlotte Haug.

She writes: “The theory behind the vaccine is sound: If HPV infection can be prevented, cancer will not occur. But in practice the issue is more complex. First, there are more than 100 different types of HPV and at least 15 of them are oncogenic. The current vaccines target only 2 oncogenic strains: HPV-16 and HPV-18. Second, the relationship between infection at a young age and development of cancer 20 to 40 years later is not known.”

Dr Haug argues that the net benefit of the HPV vaccine to a woman considering taking it is “uncertain”. But the risk versus benefit calculation for women would seem to quite plainly favour vaccination, given the very low risk of adverse reaction identified both here and in the US. While regular screening for cervical cancer is still recommended for Gardasil recipients, having been vaccinated against two common strains of HPV that can cause cancer has to amount to a greater level of protection, which kills around 60 women a year.

A second paper in JAMA raises some valid questions about the marketing of Gardasil in the US and the medical associations who received funding from Gardasil’s maker Merck to promote HPV vaccination. This is an important issue to do with disclosure of funding and transparency and is an area that deserves more scrutiny across the health sector. However, in the case of New Zealand, the entire HPV vaccination campaign was handled by the Ministry of Health and was funded by the taxpayer.

One thing becomes clear from the JAMA analysis – Merck’s US marketing campaign, which focused solely on preventing cervical cancer rather than on preventing spread of a sexually transmitted disease, was very successful and was similarly replicated in the New Zealand Government’s own campaign. After all, the Ministry of Health told me, surveys showed that the majority of the target market for Gardasil didn’t even know what HPV was.