A select committee will consider the risks and benefits of seabed mining in New Zealand waters.

The effects of mining on ocean life and the environment will be weighed against the need for metals crucial to the production of “green technologies”.

Note: The SMC has previously gathered comment on the government’s decision to back a moratorium on seabed mining in international waters.

The SMC asked experts about topics the select committee might face.

Professor Paul Myburgh, School of Law, AUT University, comments:

What issues will the select committee inquiry have to weigh up?

“I suspect the core problem is that the purposes and ideologies underpinning the various pieces of domestic legislation currently in play do not align.

“In particular, the Crown Minerals Act 1991 operates largely on an economic model – the Crown issues permits to companies to undertake economic activities to exploit mineral resources in our EEZ. The Crown is entitled to do so under international law, which generates rather handy revenue for the Government.

“The Resource Management Act 1991, and the Exclusive Economic Zone (EEZ) Acts are of course much more focused on the ‘conserving’ aspect, and this generates tension within the legal framework.

“It seems rather counter-intuitive and inconsistent (shades of the pound of flesh in the Merchant of Venice) to grant a licence to survey and exploit on the one hand, and then when a valuable resource is found, to say on the other hand, ah, but we won’t let you touch it because you will cause material harm to the environment. In a sense, the Crown Minerals Act is writing out cheques that the EEZ Act and the Resource Management Act will not cash.

“So, I think at the most fundamental level, the relationship between the Crown Minerals Act and the two marine environmental statutes needs to be explored so that any future granting of permits and consents follows a logical and consistent process. I suspect the difficulty for the Government is that the Supreme Court’s interpretation of the EEZ Act has in effect made seabed mining in New Zealand’s EEZ impracticable or even impossible, at least if it involves significant dredging and/or dumping.

“I don’t actually see that there is much room for manoeuvre here, especially in an election year, which is probably why this hot potato has been passed to a Select Committee inquiry. I suspect the most likely outcome is a protracted inquiry that lasts until the election, or the announcement of at least an interim moratorium that kicks the can to the next Government.”

How have other countries considered seabed mining?

“To my knowledge, most coastal States have to date been very cautious about allowing any seabed mining within their EEZs. Only a handful have actively engaged with the prospect.

“I am aware of active seabed mining contracts in place off the coast of Namibia (extracting diamonds and phosphorites) and prospecting contracts for phosphorites off the coast of South Africa.

“The most high profile seabed mining project to date, by a Canadian company, Nautilus Minerals, off the coast of Papua New Guinea encountered significant resistance from the local community and ended disastrously. Its collapse seems to have produced a consensus in the Pacific Islands Forum that this is not the way to go, which has also informed their leadership in calling for a moratorium on seabed mining in international waters too. So these are not exactly encouraging precedents!”

What are the legal differences between seabed mining in NZ waters vs international waters?

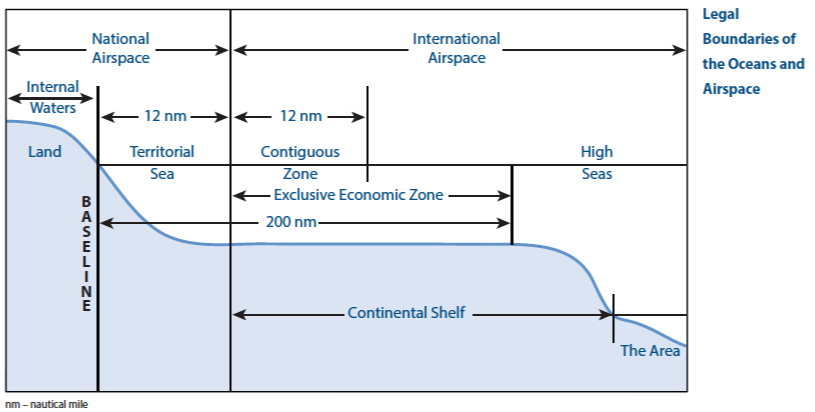

“Seabed mining in international waters – the high seas – falls within the jurisdiction of the International Seabed Authority (ISA), an international body based in Jamaica, set up under the auspices of the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS). ISA has been working for several years on a Mining Code, which would regulate prospecting, exploration, and exploitation of marine minerals in the international seabed. This has been a very slow process, but things eventually came to a head at the end of last year, when ISA said it would start processing permits in July this year. Several States, led by a strong Pacific contingent, then called for a moratorium on seabed mining until the international community has better scientific evidence on its environmental effects. Last year, the Government decided to support that moratorium.

“Any seabed mining within our territorial seas and continental shelf area is governed by our domestic statutes (NZ law). Anything outside that area will be governed by public international law (UNCLOS) and the ISA. NZ has input in the ISA as a member, but ultimately it will be an international decision made by that body.

Image: (c)Tufts University

“This means that the Select Committee inquiry is not “bound” in any way by Nanaia Mahuta’s decision to back the international moratorium on ISA approving permits – they could theoretically recommend that seabed mining go ahead in some form within the confines of the NZ continental shelf and argue that seabed mining in international waters is a different kete of fish.”

No conflict of interest.

Professor Jonathan Gardner, Professor of Marine Biology, School of Biological Sciences, Victoria University of Wellington, comments:

What kind of seabed mining could happen in New Zealand?

“There is existing coastal mining going on in New Zealand right now. For example, sand mining in shallow waters occurs at Pakiri Beach, north of Auckland. This sand is used mostly for concrete.

“In mid-water regions such as the Taranaki Bight off south Taranaki there is a proposal to mine iron sand. The naturally-occurring iron would be removed from the sand and shipped to China whilst the sand itself will be returned to the seafloor.

“There is also a proposal to mine phosphate-rich nodules (for use in agriculture as fertiliser) from the Chatham Rise but this has not yet commenced.”

How might seabed mining affect marine ecosystems?

“Most obviously, any rock extraction process is going to break up and grind the rock, thereby removing the natural surface on which organisms live. The mining machines themselves are large and heavy and will cause direct impact by crushing animals. The removal of nodules will change the seafloor by exposing sediment which previously was not exposed to water movement, and this may change the flow of water over the seafloor itself.

“This could affect the movement of oxygen and food and the removal of the animals’ waste products from the immediate deep sea environment, and reduce the amount of ‘structure’ on the seafloor. Typically areas that have more ‘structure’ tend to be characterised by greater biodiversity so loss of structure often leads to loss of biodiversity.

“The removal of sand or sediment will kill organisms associated with the surface as well as animals that live in the sand. Thus, we know that there will be considerable direct mortality of individuals and communities resulting from all forms of mining.

“All of these extraction processes are going to create sediment plumes, either directly at the bottom where the point of extraction occurs, or in the water column when the spoil is returned to the marine environment. Sediment plumes may be short-lived or long-lived, depending on the local conditions and currents, but generally these sediment plumes will smother animals and/or clog their delicate feeding and respiration surfaces.”

Note: Professor Gardner previously commented for the SMC on international deep-sea mining regulations.

Conflict of interest statement: “I am a Professor of Marine Biology at Victoria University of Wellington, working on (among other things) deep-sea genetic connectivity. I work very closely with NIWA and my research has been jointly funded with NIWA. I have received funding for deep-sea genetic connectivity work from MPI and MBIE. I am on the Technical Advisory Board of CIC Ltd – a deep-sea mining company. I am a Trustee of The Guardians of Kapiti Marine Reserve.”

Professor Chris Bumby, Principal Investigator at the MacDiarmid Institute for Advanced Materials and Nanotechnology; and Chief Scientist (Materials) at the Robinson Research Institute of Victoria University of Wellington, comments:

“Metals are essential materials for the modern world, and without them our society would look very different. Metal components underpin infrastructure, construction and most manufacturing industries. In addition, there are a class of ‘critical metals’ which are essential ingredients for key electric technologies such as: batteries, generators, electric motors, photovoltaic cells and more. There is an urgent need to produce more of these metals right now, in order to rapidly decarbonise the transport and energy sectors.

“In almost all cases, today’s demand for industrial metals substantially exceeds the volume of ‘end-of-life’ material available for recycling. Meeting demand therefore requires new primary production from mineral deposits – and this situation will persist for decades to come. Uptake of new climate mitigating technologies will inevitably require more mines at locations where specific mineral deposits naturally occur. Mining anywhere always involves trade-offs, weighing local environmental degradation against other benefits (which are often more dispersed). This is the case in the marine environment, just as it is on land.”

What metals are present in the seabed around NZ, and what are they used for?

“Mineral exploration of the global seafloor is still in its infancy, and there remain large gaps in our knowledge of potential seabed resources. Despite this, there are several known mineral deposits within NZ waters. These include deposits of vanadium, cobalt, manganese, zirconia, iron, titanium, and phosphates. Future research may well uncover additional resources that are yet to be discovered.

“Vanadium is an important component in modern high-strength steels. It is also an irreplaceable component in aerospace alloys and orthopaedic implants (hips, knees etc.). In addition, vanadium flow redox batteries (VFRB) have recently emerged as the front-runner technology for future grid-scale batteries – but uptake is currently limited by the low volumes (and high price) of vanadium on the global market. Global production of vanadium today is about 120,000 tonnes per annum, with 80% of that is located within Russia and China. NZ is estimated to have several million tonnes of offshore vanadium resources present within ironsand deposits found up to 40 km from the North Island coast. These same deposits also represent a substantial iron ore resource.

“Manganese-cobalt nodules can be found in some areas of the South Pacific seafloor – where they lie freely available on top of the seabed. Cobalt is an essential metal for Li battery electrodes and specialist steel alloys. But ~70% of current global supply is sourced from a large deposit in the Democratic Republic of Congo – a conflict zone in which human rights abuses are well documented. Manganese deposits are more widespread but this is also a critical metal – used as an alloying input for stainless steel, as well as in some battery chemistries.”

Conflict of Interest statement: Prof. Bumby currently leads an MBIE-funded research programme investigating “Zero-CO2 production of technologically essential metals”. He has also previously undertaken commercial R&D projects for several NZ companies investigating the production of industrial metals from both waste slags and mineral resources.

Professor Nicola Gaston, Co-Director, The MacDiarmid Institute for Advanced Materials and Nanotechnology, comments:

“The prospect of seabed mining is an emotive one, with the prospect of environmental damage rightly at the top of many people’s minds. However it is worth keeping in mind that mining, in different forms, is necessary for the supply of many materials of technological and societal importance. While the recycling of precious elements is an emerging and exciting technology – the work of kiwi company Mint Innovation in extracting gold from dumped computer waste is a great example – it is not yet a practical option for many materials that we rely on, either because the technology still needs development, or is not economic, or because current demand for the material exceeds the amount available to be recycled.

“While banning seabed mining will avoid associated environmental damage in Aotearoa, it does not necessarily mean minimising the environmental costs of the materials in the products that we buy. One might even say that the argument for mining in New Zealand should be less about the economic opportunity, than about the potential to price in any costs of environmental remediation through legislation. However, whether we are positioned to do that well is a key question, and perhaps an even bigger question in the context of seabed mining than in the case of mining on land.”

Conflict of interest statement: Nicola Gaston is the Co-Director of the MacDiarmid Institute for Advanced Materials and Nanotechnology, which receives government funding for research into materials for sustainability.

Professor John Cockrem, School of Veterinary Science, Massey University, comments:

How might seabed mining affect seabirds?

“Digging in the seabed creates dirty water which can extend over very large areas. That dirty water would reduce the foraging opportunities for seabirds, and would have adverse effects on marine life. These include kororā (little penguins), fairy prions, and threatened species like the flesh-footed shearwater. I outline the evidence for this in my submission to the EPA in 2017..

“What’s become dramatically apparent since I commented in 2017 is the effect of climate change on the marine environment, with changes in weather and sea surface temperature. Any modeling that might have been done about where dirty water plumes might go and how dense they would be, that modeling is based on previous data and cannot predict what will happen in future when the situation out on the seas is changing. Indeed with the changing weather patterns, ocean currents in 10, 20, or 30 years time, could well be different from what they are now. The modeling that’s done based on past data is not valid for predicting the future in 2023.

“Climate change also means the seabird populations are going to be, as time goes on, more and more vulnerable to adverse effects created by dirty water from seabed mining. Their day to day existence is becoming gradually harder and harder. This is owing to changes in food availability that can come from changes in sea surface temperatures, leading to changes in the extent to which nutrient-carrying colder water is upwelling to the surface.

“Seabirds are facing a much more precarious existence in coming decades, than was the case before. And so seabed mining should not happen in New Zealand waters under any circumstances.”

Conflict of interest statement: In 2017 Professor Cockrem provided evidence to the EPA about adverse effects of sand mining on seabirds and was an expert witness for KASM and Greenpeace.