New Zealand’s nine extinct moa species were surprisingly diverse in their diets, reveals sophisticated 3D modelling research from New Zealand and Australian scientists.

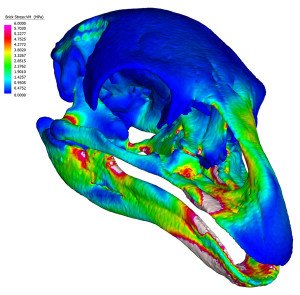

A new study, published in the journal Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences, uses 3D scanning technology to create models of moa skull structure based on fossilised remains of the extinct birds.

These were compared between moa species and to two living relatives, the emu and cassowary. The models simulated the response of the skull to different biting and feeding behaviours including clipping twigs and pulling, twisting or bowing head motions to remove foliage.

The researchers found that there were more differences than expected in how moa harvested and ‘chewed’ food, suggesting that they each exploited their local habitats and evolved unique feeding strategies that may have been specific to certain plants.

You can read more about the research on Scimex.org.

The SMC collected the following expert commentary. Feel free to use these quotes in your reporting.

Dr Mike Dickison, Curator of Natural History, Whanganui Regional Museum, comments:

“You’ll frequently read in Stuff comments and on Facebook that deer are just doing the same ecological job that moa once did. A study of exactly how moa ate is one way of testing if this is true.

“We already knew that several species of moa lived side by side almost everywhere in New Zealand, and that they had very different body sizes, diets, and bill shapes – some of this paper’s results are not news. But this mechanical analysis of their bills suggests moa had a wider range of feeding strategies than we thought, and most must have fed in a very different way to living giant flightless birds such as the cassowary and emu.

“This is important, because emu have been suggested as an possible ecological surrogate that could replicate the effect of moa browsing in New Zealand forests. Emus have even be been used experimentally to test if our plants are adapted to resist moa browsing, but those experimental results look more dubious now.”

Dr Daniel Thomas, Lecturer in Vertebrate Zoology at the Institute of Natural and Mathematical Sciences, comments:

“This study has used advanced techniques that were originally developed by engineers to help us understand how the community of moa species could coexist, and we have been reminded that different moa species ate different types of plant.

“From preserved moa dung and the shapes of moa skulls we knew that moa species must have had different diets, and these skull stress data give further support to that idea.

“This study gives us new insight into the structure of plant and animal communities in ancient New Zealand.”