The Australian Bureau of Meteorology has confirmed the Pacific is in an El Niño climate pattern – what does this mean for New Zealand?

The Bureau made the declaration yesterday following close analysis of ocean temperature shifts and wind patterns.

The Bureau made the declaration yesterday following close analysis of ocean temperature shifts and wind patterns.

The El Niño conditions typically bring warmer ocean waters in the tropics, and weaker wind patterns, resulting shifts in climate around the Pacific.

You can listen back to an AusSMC briefing with Bureau meteorologists announcing the El Niño pattern on the AusSMC website, or read an explainer published on the Conversation website.

The SMC NZ collected the following expert commentary.

Professor James Renwick, School of Geography, Environment and Earth Sciences, Victoria University of Wellington, comments:

“El Niño has finally come again, after nearly making it in 2014. An El Niño happens every few years when the waters of the tropical eastern Pacific warm up and the Pacific trade winds slacken off. Last year, we had the ocean warming but the trade winds never got the message.

“This year things seem to be coming together better and an El Niño event should strengthen over the next several months, and last through the end of the year. Although an El Niño brings weaker winds and warm seas in the tropics, New Zealand feels the opposite – on average, the seas around New Zealand cool off and the westerly winds that dominate our climate strengthen, and turn more to the southwest.

“If things go the way of an ‘average’ El Niño, we would see cooler than normal temperatures in many places in the second half of the year, with the possibility of dry conditions developing in the east and north of the country. One thing we do know though: every El Niño is different, so we need to watch closely as the current event develops.”

The MetService has also issued the following commentary from meteorologist Georgina Griffiths:

El Nino strengthens

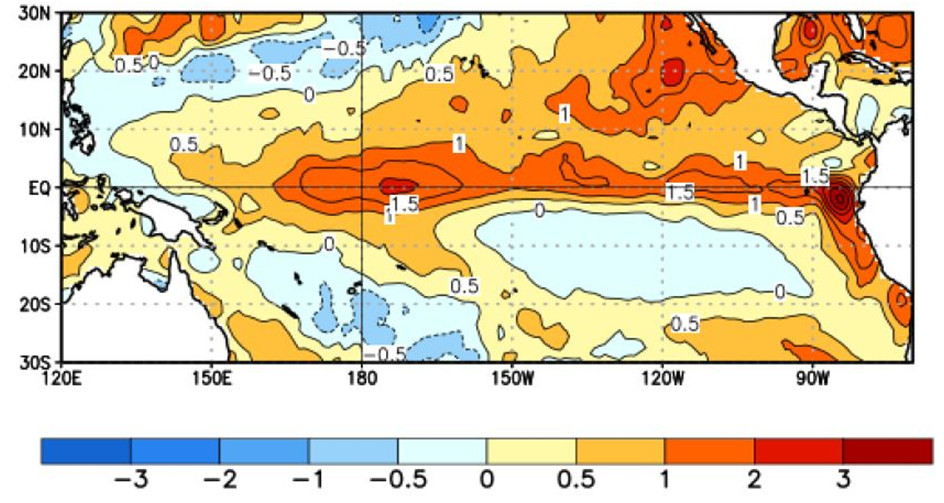

El Nino conditions have recently strengthened in the tropical Pacific Ocean. Seas along the equator are abnormally warm right across the Pacific, from the South American coast to the Solomon Islands. This unusual warmth has increased over the last few weeks, with seas now more than 2 degrees above normal near South America, and more than one degree above normal elsewhere along the equator. “This so-called ‘warm tongue’ of water along the equator is the classic El Nino signature,” said MetService Meteorologist Georgina Griffiths. “And it has intensified in recent weeks.”

The atmosphere is playing ball, too, with weaker trade winds observed along the equator. This, too, is the traditional El Nino atmospheric signal – and it alters where the rain falls in the tropics.

El Nino forecast to continue

The latest climate predictions indicate a solid chance (around 70%) that El Nino conditions will continue through the southern winter and spring. At this stage it is too early to tell whether this El Nino will be a strong event, as the models still show a fairly wide range of outcomes.

So what will it mean for New Zealand?

Seas around the New Zealand coastline are already cooling more rapidly than is normal at this time of year. This is consistent with the typical El Nino response in our region – markedly cooler sea temperatures over winter and spring. “Sea temperatures are important, because to a certain extent they influence air temperatures in our coastal towns and cities,” Griffiths commented. “But perhaps the most obvious impact El Nino brings to New Zealand is an increase in southerly to southwest winds over winter and spring.”

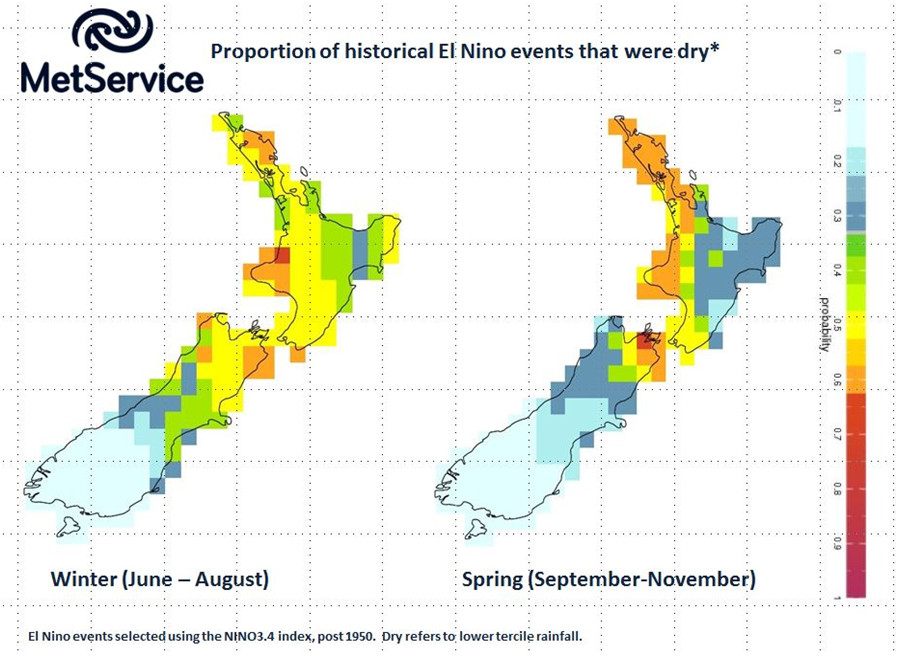

Not surprisingly, most El Nino winters are cooler than usual, right across the country. But the typical rainfall response to El Nino is more complicated, as it depends on what season and which region. “The chances of a relatively dry winter increase during El Nino for the western North Island (Northland, Auckland, Waikato, Waitomo, Taumarunui and Taranaki), as well as for Nelson and Marlborough,” Griffiths commented. “But in the North Island, we may not notice this effect very much from day to day, since winter usually yields more than enough rain!”

“Spring (September -November) is when El Nino really starts to flex its muscle here,” said Griffiths. Typically, El Nino produces a stormy, windy spring, which is often extremely cold. The chances of a wet spring are increased during El Nino in the west and south of the South Island. In contrast, the western North Island, Nelson and Marlborough, tend to be drier than usual.

And what about places like Canterbury and the eastern North Island? El Nino often, but not always, results in drier conditions in these regions once we head into summer. “These regions are impacted by El Nino towards Christmas, in fact during the driest time of year,” said Griffiths.

Always, farmers and growers should keep an eye on the short-term weather forecast at www.metservice.com and monitor the rural outlook each month at http://www.metservice.com/