Scientists have confirmed in a new research paper on last year’s disastrous February 22 Christchurch aftershock that computer modelling showed a week beforehand that there was a 25 percent chance of “a magnitude 6 or greater earthquake occurring in the general aftershock zone of the Darfield earthquake in the next year”.

The paper is available for download here.

Authors of the paper, the Mw 6.2 Christchurch Earthquake of February 2011: Preliminary Report said that time-dependent earthquake forecast models such as the Short Term Earthquake Probability (STEP) model were implemented after the 7.1 magnitude September 2010 Darfield earthquake, and forecast an aftershock “of the size of the 22 February earthquake with a high probability”. STEP was created in 2005 by Dr Matt Gerstenberger of GNS Science and his colleagues in the United States and Switzerland, and research into operational earthquake forecasting is continuing overseas.

During the Royal Commission inquiry into the Canterbury earthquakes, the issue was probed last October, when GNS scientist Dr Kelvin Berryman said that the GNS team had grappled over the merits of making a public warning: “There were five or six obvious scenarios where that future earthquake might occur. The worse possible case was directly under the city.

“It wasn’t really a reasonable approach to try and do that at that time because of the range of places where that magnitude six might occur. We didn’t want to alarm unnecessarily,” he said in October 2011.

After September 4, GNS staff noted a “social science recommendation” to provide basic numbers. But some residents were alarmed by a subsequent magnitude-4.9 Boxing Day quake, and another GNS Science researcher, Dr Terry Webb said last October that in the first couple of weeks after that Boxing Day 2010 shake, “social science advice was basically that we’ve got a traumatised population and what can you do to help them cope best, and that really was to get them coping with aftershocks”.

After February 22, GNS Science did make public statements warning of the possibility of a further aftershock of one magnitude less than the 6.3 magnitude shake which resulted in the deaths of 182 people. Earlier this year it gave a public briefing on aftershocks fading away over as long as 30 years, and Dr Berryman has said scientists should have a better picture by next week of when Canterbury’s shakes will settle into a “background” level.

Today, the journal paper — published in the New Zealand Journal of Geology and Geophysics with GNS Science seismologist Anna Kaiser as lead author — said that the Darfield tremor was a “large regional quake” and the February 22 a “close-by moderate-sized earthquake” with stronger shaking than was expected for a quake of that size.

“The ground motions were of very low probability according to the national seismic hazard model,” the authors said. “Ongoing efforts are focused on better quantifying the factors that contributed to the high ground motions in order to assess the possible implications for future earthquakes in the Canterbury region, and by extension other comparable areas in New Zealand and worldwide”

Key points included:

- Horizontal ground motions 1.7 times the force of gravity were larger than expected.

- One reason for this was the rupture’s “directivity” towards Christchurch.

- A trampoline effect enhanced by the “slapdown” of falling upper soil layers hitting rising sub-soils.

- “Remarkably high” levels of apparent stress: two possible reasons are canvassed.

- High water tables trapped energy in the top layers of soil in some areas, boosting liquefaction.

- The Banks Peninsula volcanic outcrop may have concentrated the stress field.

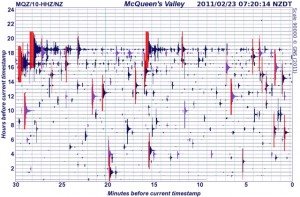

- Data from 129 of Geonet’s sites created the most significant dataset since strong-motion recording began 50 years ago.

- And 17 ground and structural records from within 10km of the fault are prized: most Wellington is also within 10km of a fault(s).

- Liquefaction caused the largest damage to land and buildings, including many CBD high-rises.

- Deep-seated landslides caused most damage in the southern Port Hills.

- Critical structural elements in buildings 1976-1992 failed, staircase damage was severe in some post-1992 buildings.