Contamination from waste and litter dumping, deep-sea mining and fishing, and climate change are among the threats outlined in a new report released by experts calling for greater attention to be paid to major human impacts on the deep sea.

More than 20 scientists — including two from New Zealand — are making public a list of the most vulnerable deep-sea habitat types, published today in the journal PLoS One.

Over 2/3 of the planet’s surface is covered by ocean, reaching depths of over 3000 metres across more than half this area. This largely unexplored frontier is subject to increasing stresses and degradation from human activities.

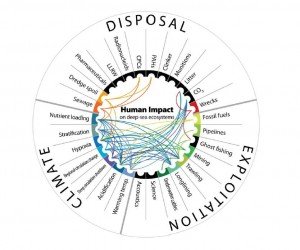

The researchers found that while dumping of rubbish into the sea had traditionally been a major problem, it was being replaced in importance by the exploitation of the undersea environment and most significantly, ocean-wide changes caused by climate change.

“The analysis shows how, in recent decades, the most significant anthropogenic activities that affect the deep sea have evolved from mainly disposal (past) to exploitation (present),” they write in PLoS One.

“We predict that from now and into the future, increases in atmospheric CO2 and facets and consequences of climate change will have the most impact on deep-sea habitats and their fauna.”

Deep sea environment types most at risk:

1. Sedimentary upper slope benthic communities: climate change will have a major impact, particularly caused by the confluence of changes in nutrient input, ocean acidification and spreading of hypoxia. Furthermore, because of the immense global fishing effort on slopes to 1000 m depth, this habitat is, and will be, greatly affected. Although historically these areas have received the most protection from fisheries (e.g. conservation areas), continued efforts to protect vulnerable margin communities against negative impacts of fishing are necessary.

2. Cold-water corals: fishing activities and ocean acidification caused by climate change will be the major impacts affecting cold-water coral communities.

3. Canyon benthic communities: these are mainly affected by fishing activities as improved technologies enable the exploitation of rough terrain such as that found in canyons. Another major impact in canyons will be the accumulation of litter and chemical pollution, accentuated by the conduit effect of canyons and large-scale episodic events such as dense shelf water cascading. Climate change will add pressure to canyon benthic communities by affecting circulation, stratification and nutrient loading.

4. Seamount pelagic and benthic communities: fishing effects on demersal and pelagic species and fishing damage to benthic communities and habitat will greatly affect seamounts, together with changes in global and regional circulation and stratification caused by climate change.

During the Census of Marine Life, a decade-long programme that investigated diversity, distribution, and abundance of life in the global ocean from 2000 – 2010, researchers from its five deep-sea projects sampled and studied deep-sea habitats around the globe. The new paper analyses the findings of these Census of Marine Life projects and previous literature to paint a comprehensive picture of risk factors and human impacts.

Dr Charlotte Severne, Chief Scientist – Oceans, NIWA comments:

“The seafloor around New Zealand is rich in deposits that contain valuable minerals and metals. It is important that these resources are utilised sustainably ensuring that we take steps to protect the deep-sea biodiversity. Baseline studies of the seafloor biota including monitoring prior and post activities will assist planning and the formulation of regulation thus reducing longterm risk to vulnerable deep sea communities.

“So much of New Zealand’s deepsea is unexplored. Reducing risk to ecosystems of our deepsea canyons, seamounts, hydrothermal vents, cold seeps, abyssal plains and trenches that we have none or little knowledge will require policy, industry and scientific analysis. We have the time to put in place effective environmental management of New Zealand’s deep sea.”